Urban Technology at University of Michigan week 66

The past and future of civic finances

How do cities raise money? It’s a simple question, but it can be answered—and has been answered—in a myriad of ways. Today we explore different ways cities have tried to raise money, see what challenges Detroit is facing, and explore new approaches, enabled by technology, that might offer alternatives for funding civic efforts.

Hello! This is the newsletter of the Urban Technology program at University of Michigan, exploring the ways in which technology can be harnessed to nurture and improve urban life. If you’re new here, try this 90 second video introduction.

⚡️ Interested in this stuff and also a designer, coder, or other proactive spirit? Apply for a Prototype Grant, due Nov 15. ⚡️

💰 Death and Taxes

Taxes are, of course, as old as time. Although the earliest approaches to taxation were often per person (a head tax), taxing land soon became a more common approach. In 8th-century China, the Tang dynasty shifted from per capita to land-based taxation, which allowed large estates to be taxed based on their large footprint rather than the small number of (wealthy) individuals living there. Rural lands were also traditionally taxed more heavily compared to urban areas. In Egypt during the Ottoman Empire, for instance, 67% of the state’s revenue came from land taxes, compared to a mere 7% from taxes on urban merchants and artisans.

That said, cities frequently attempted to tax assets beyond tracts of land. In Renaissance Italy, Florence had long imposed direct taxes on land, particularly in the countryside, but those efforts failed to capture other, more liquid forms of wealth—which became an issue as the number of wealthy merchants in the city grew. Faced with increasing fiscal pressures and revenue shortfalls, in 1427 the city organized a massive survey to correctly evaluate the taxable potential of each household.

How did it work in practice? Nine separate boards of assessors assigned a value to every home. The three highest and three lowest estimates were then discarded, and the three remaining were averaged. Was the system perfect? Hardly: even contemporaries protested the commissions’ miscalculations. Were the assessors impartial? No: friends, family, and patrons all benefited from their personal relationships. But it represents an early attempt to improve a city’s tax revenue and manage the city’s public debt—called the monte, or “mountain,” due to its size.

An alternative approach can be found in seventeenth-century England, with something known as the “hearth tax”: taxation based on the number of fireplaces in a household. It represented a somewhat progressive approach, since the number of fireplaces should correspond to the size of a residence and, thus, its wealth. Poorer and rural households that had fewer fireplaces would avoid paying substantial sums. But it begs the question: how did officials actually know the correct number of fireplaces in a given residence?

Did they enter every house and count them, room by room, hearth by hearth? Luckily, there was a handy shortcut: chimneys. Since chimneys were attached to a fireplace and visible from the road, an official could count them and assess a house’s taxable value without entering. (For what it’s worth, the hearth tax was still wildly unpopular.)

There are many other examples of intangible tax regulations shaping the built environment. Mere decades after the hearth tax, a “window tax” was imposed in England that functioned much the same (initially 4 shillings for up to 20 windows, or 8 shillings for 21 or more, though this was modified repeatedly). Or consider a French example: when the city of Paris enacted a law restricting building heights in 1783, a building’s height was only measured from the ground to the cornice. Expansions of Mansard-style roofs allowed for additional, tax-free living space to be constructed above:

In the U.S., taxes at the state level—typically a combination of income and sales taxes—have existed since the country’s founding. Cities, though, depend heavily on property taxes. Over time some larger cities have supplemented this with local sales taxes (beginning with New York City in 1934) and local income taxes: Philadelphia did so first, in 1938, and was followed by other major cities, including Detroit in 1962. There are other revenue streams for a city, ranging from building permits to parking tickets, but property and other local taxes are almost always the base—check out this visualization of the city of Oakland’s revenue streams and expenses, with revenue sources listed on the left side below. So, if a city relies heavily on property taxes, what happens when there are severe declines in property values?

💸 Motor City Money

Between 2000 and 2012, the number of jobs available in Detroit declined by 43%. The city’s population has declined by over 1 million people since 1950. And property values have declined sharply, even with some recovery following the Great Recession. All of those statistics add up to a real problem for the city’s finances. A decline in employment opportunities means less commercial revenue to tax, and less personal income that can be taxed. People moving out of the city means a smaller population base, and fewer occupied residences that can be taxed.

Given this situation, if you’re a member of the Detroit City Council, what options do you have to increase revenue? Raise taxes? Detroit already has the highest property taxes in the state, and is among the highest rates of any major city in the country. Even if you did want to raise property taxes, there are state-imposed limits on how much can be raised by local communities.

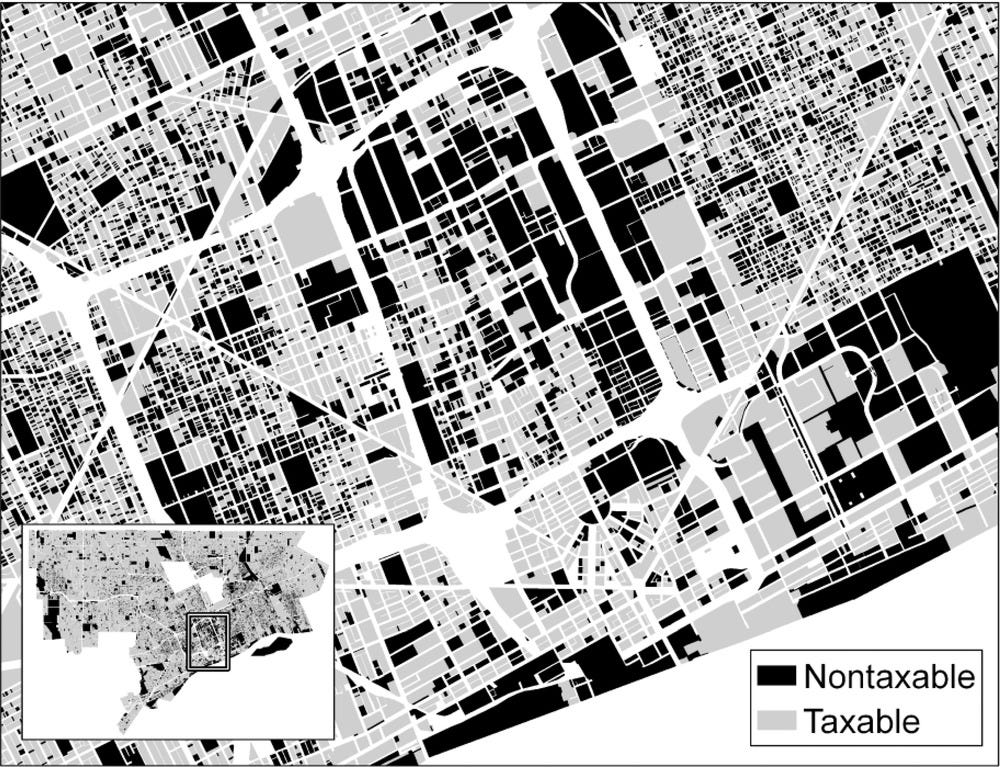

There are other challenges with what the city can tax. Detroit has granted different tax abatements to encourage redevelopment of distressed areas—but such efforts to encourage economic growth mean decreased tax revenue for the city. (For areas designed as a “Renaissance Zone,” residents pay no personal property tax, income tax, or utility tax.) Tax delinquency decreases the amount of money coming into the city, of course, but tax-foreclosed property also reverts back to public ownership, and is no longer taxable (in addition to other downsides). Vacant lots, whose number has increased since 2000, represent another missing source of potential revenue. Taken together, these all add up to large areas of missing revenue in the city, as this image from a paper by Gary Sands and Mark Skidmore shows:

To bring it back to our initial question: how can a city raise money to pay for things like new infrastructure, public transit, or other services—especially if property taxes are limited? What other options exist, and how might technology create new possibilities?

🤑 Civic Crowdfunding

Civic technologies allow citizens to be much more involved in local governments in a variety of ways—and for governments to be better connected to local input and feedback. The same may hold true for financing. Can crowdfunding platforms change the way that funds can be directed toward community projects, or even public works?

One platform, called ioby (In Our Backyards), allows community residents to propose ideas for projects that are then open for online donations, and ioby, in turn, pledges to work with each campaign to design their crowdfunding strategy. Since 2016, projects in Detroit have raised over $730,000 in donations for things ranging from building community centers to supporting art festivals, promoting urban gardening, and much more.

In their words: “Our simple goal is to put cash in the hands of Detroiters with good ideas [...] Quickly-funded, small-scale, highly visible neighborhood projects have a way of bringing people together and strengthening networks of neighbors.” Is it a substitute for funding from local governments? No. But it is a bottom-up, technology-enabled way for citizens to directly fund things that matter to them, including the types of things that may never even be considered by local government.

If ioby works largely independently of local governments, Patronicity offers a way for citizens to partner with civic officials and other entities to crowdfund placemaking projects. Here in Michigan, the Michigan Economic Development Corporation (MEDC) worked with Patronicity to support an initiative called “Public Spaces, Community Places,” in which nonprofits and municipalities seek financial support for projects including public art, parks, trails, and other public spaces. If they crowdfund half of their funding goal, the other half is matched by MEDC.

The results? Nearly $11 million in crowdfunding from 51,000 different patrons, matched by $9.5 million from the MEDC. That’s an incredible impact, with little direct investment from local governments. But more than simply saving the government money, Patronicity’s approach ensures that local communities have a voice in shaping their communities, and it encourages deeper engagement between governments and some citizens.

So, will urban technologies like crowdfunding replace tax dollars as the mechanism to pay for public needs? Not likely and, unless the crowdfunding platforms change, not equitably. Crowdfunding too often privileges the folks who have funds to contribute and the time to do so. How could the model be adjusted to create opportunities for people without spare cash to contribute?

As much as raising money for a local initiative is encouraging, having a say in what happens in your own backyard is even more critical. If platforms like ioby and Patronicity evolve with collaboration from local government, it’s possible to imagine digitally-facilitated participatory budgeting, which is a community priority-setting and self determination approach that emerged out of Porto Alegre, Brazil in the 1980s. Such a combination would bring governance and finance back into the same discussion—letting communities articulate their own priorities and pairing those articulations with actual funds.

The potential upside goes beyond finding money for things that otherwise would not be funded. London conducted a five-year crowdfunding pilot and found that 77% of those involved felt more empowered as a result of crowdfunding for their project and 72% of projects said the experience increased community cohesion, both important and so hard to come by at this point in time. Then again, is it really so surprising that giving people more of a say in what happens in their own neighborhood also makes them feel better about themselves and their neighbors? This is why governance is so important to us when we get excited about technologies that empower, restore, nurture rather than extract, marginalize, and exclude.

So who else is excited about the intersection of funding and governance in a single technology? The crypto legions! Next time we’ll take a look at emerging developments—the good, the bad, and the confusing—where the block in “blockchain” is not an abstract mathematical concept, but a real place.

Links

👀 Podcasts for deaf people? Vox Media has created crazy expressive scrolling transcripts for More Than This. Here’s an example and here’s a note (in ASL and written english) from one of the designers who made this beauty happen.

🪵 If you like doing things differently, how about wooden nails? Chemical and pressure treated wood that's harder than steel.

🚴 How do you make your own school bus? With children! Barcelona’s Bicibus is the content you need on this rainy, dark Friday. “It started last month when some parents organized a bike ride to school for just five kids. Now entire neighborhoods are joining.”

🚶 “We recognize not everyone will always feel safe taking a purposeless walk, but hope this serves as a reminder that you absolutely have the right to do so.” Wander Prompts by H.Jaramillo and C.Joerges will help you do nothing.

🥽 Niantic Labs launches a new AR game with Nintendo and Facebook sidesteps recent turmoil by betting it all (including its name) on the metaversere, announced during a mega keynote. We’ll save the criticism for Twitter (though this pre-drag from Niantic’s CEO is good) but one hot take: an internet that tries to overcome the limitations of spatial reality is hokey, escapist, and problematic in plenty of ways but it’s far more interesting than an internet that ignores spatial reality altogether, like the era of social media did.

These weeks: lining up a workshop and lecture with George Aye of Greater Good Studio,. Curriculum tinkering. Meetings (obviously). Had the 3rd and 4th of four lunchtime panel sessions. Carving gears, finding levers. Machine half built. 🏃