Have you ever seen a piece of paper taped up on the entrance to a building or above the buttons in an elevator lobby that bluntly communicates, “that thing you think you can do here, it has to be done elsewhere.” Yes, you have; in the form of signs emblazoned with phrases like USE OTHER DOOR or XRAY DEPT → or ACCESSIBLE ENTRANCE AROUND BACK.

These ad hoc notes taped up on buildings and in the public realm are the most prevalent form of post occupancy analysis, which is the term of art for systematically checking to see if the thing we built performed in the ways that we designed it to perform. Reader: very little of the built environment is studied systematically after completion to verify things like actual ease of wayfinding, actual energy performance, actual productivity or serendipity or whatever benefits of the design were promised by a dashing designer in the board room. Architectural design is a profession with a surplus of charisma masking the fact that it exists in a condition of data poverty. The data simply doesn’t exist.

Over the summer we interviewed teams within design firms about how they’re building their own digital tools to take advantage of data they collect or simulations they build, all with the goal of enabling better design decisions. For all the attention paid to AI automating office jobs right now (including design roles), what was most exciting from our research this summer were the examples where a human was in the loop. In fact, that may be the whole point. As firms move to adopt data-infused workflows, this represents a significant culture change whether they know it or not: new data means new tools, means new ways to evaluate work as good or bad, means eventually new kinds of talent are going to thrive in these environments.

Below the jump we are sharing an excerpt from our discussion with Aaron Woolverton at Design Workshop, a landscape architecture firm working in the mountain west and beyond. One thing I found notable from our talk is that he did not refer to monolithic software from the likes of Autodesk, a behemoth in the AECO space. Instead, the future Aaron describes is one of firms building their own workflows, stringing together existing libraries with unique vibe coded modules, merging data sets, and having enough talent in house to make it all bespoke. An ecology of software to design an ecology of spaces, perhaps? Count me in.

💬 Hello! This is the newsletter of the Urban Technology program at University of Michigan, in which we explore the ways that data, connectivity, computation, and automation can be harnessed to nurture and improve urban life. If you’re new here, try this short video of students describing urban technology in their own words.

🌳 Six Questions for Aaron Woolverton

Aaron Woolverton is coordinator for the 16-member DigiLab, which is part of the landscape architecture firm Design Workshop. The DigiLab team explores digital tools and data to enhance design workflows within the Workshop’s projects, spanning from intimate gardens to large-scale master planning efforts. Over the summer we got Aaron on the horn to learn about the digital workflows he’s building.

Bryan: My observation is that a lot of digital work in architecture design firms is script-based and doesn’t have a UI per se, but you’ve spoken about building tools for your colleagues, so the UI becomes critical—is that right?

Aaron: Yeah, that’s totally right, and in a way, that’s kind of what DigiLab is too. We’re trying to create a more standard and universal approach to integrating [tools that use data to accelerate the design work]. Working with data is very quick if [the tools are] set up correctly. [We work on] formulating best practices and [building] a universal workflow. I would credit Chris Landau because he’s the one who built Human UI [which is a tool to create user interfaces that we use in our] workflows. There are maybe like 10 people in the firm who would open a programming environment like Grasshopper and feel comfortable, so being able to build a UI is important.

Bryan: Right, because scripts are still pretty much for power users but UI makes computational power accessible to more users. What kinds of problems are the new tools and interfaces you’re building helping the firm solve?

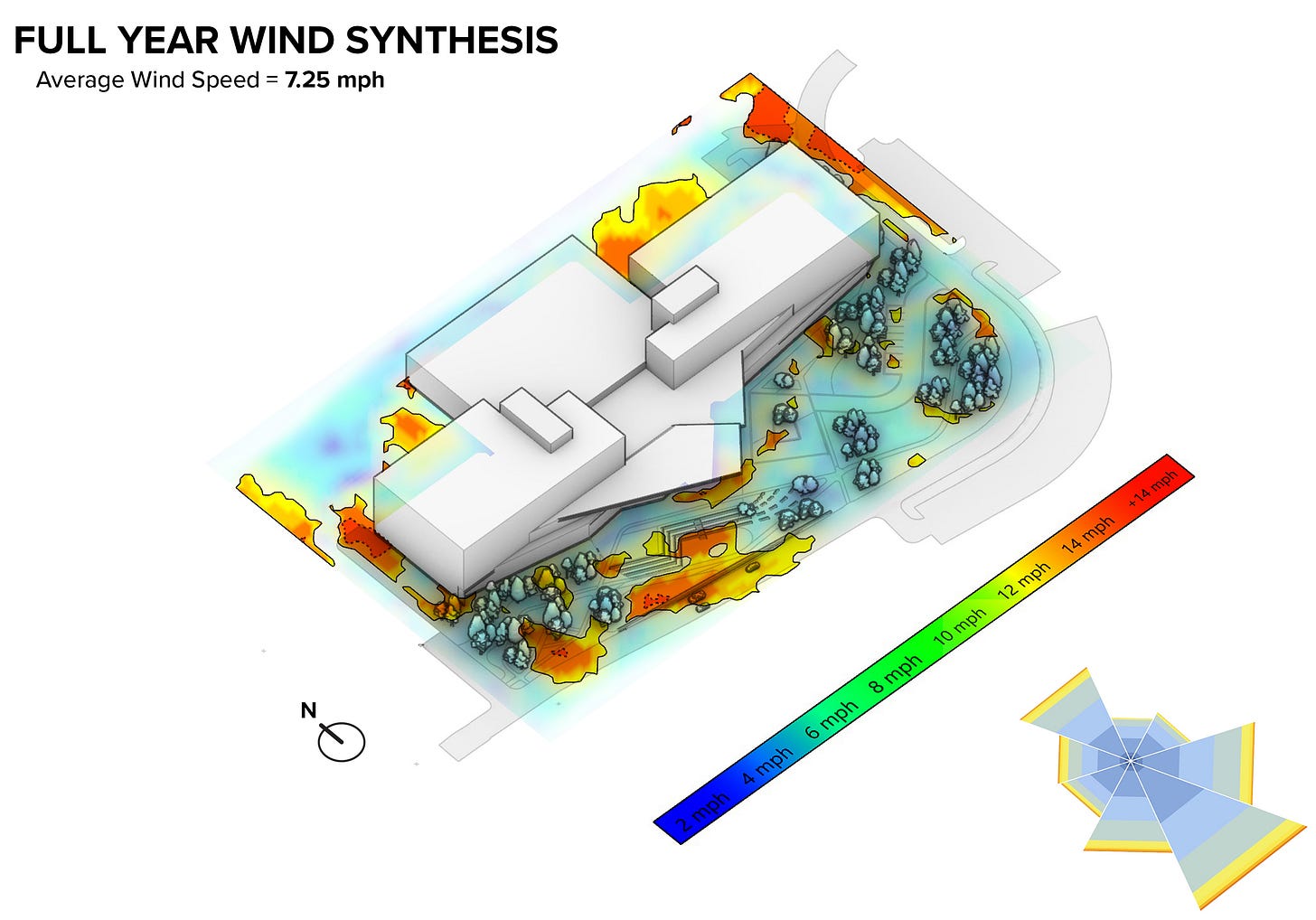

Aaron: A lot of our work and a lot of what we’re trying to move into has to do with questions like thermal comfort. We’ve been using tools like Ladybug to map and analyze how our designs [would] effect and be effected by the environment [such as wind dynamics]. If you’re sitting down on the park bench and there’s a wind speed greater than maybe 6 meters per second per second, it is going to be considered uncomfortable by most people. So we’d like to be able to create an interface that updates as you’re moving trees around, or moving a building site around, to get a sense of how like wind will move through the site.

Bryan: What is the missing data set that if you would create if you had a magic wand?

Aaron: It would be all about plantings from more of the landscape point of view. Some exist, like the ERA database, and it is actually pretty extensive. It tries to cover the native species throughout the country and stuff like that. But very often, especially with landscape architects, we’re working with adapted plants due to a variety of reasons—it could just be aesthetics, it could be [that] adaptive plants actually can perform better in [a given locale].

Bryan: What are some examples of the missing fields then, if you were to add them to the database you mentioned?

Aaron: It has things like soil properties including ph levels, but I would want more of a mutualism kind of category. What does this plant work well with? Which plants could it provide to or receive nutrients from? Who are its best pollinators? How does it performs as part of an underground network, [but that’s] relatively new science!

Bryan: What kind of expertise do you think DigiLab will need in 3-5 years?

Aaron: With everything we’ve been talking about, UI/UX [is important]. I think people who who can write in python and writing code would be helpful, [but maybe even more so is] literacy and knowing how to get the most out of [AI tools] to facilitate a process. I think a lot of people in my firm think our group is about visualization and graphics, so it I try to like demystify a little bit of that and speak more about data integration [in the design process]. Because of this, people who really understand data [structures] and databases are also who we will be looking for.

Bryan: What’s your favorite city, and why?

Aaron: Philadelphia! 100%! I am a Philly lover. It’s so walkable.

These weeks: UT++ workshop. Cities Intensive field trip to Detroit. More thinking about studio space. Planning some travels for the spring. 🏃

If an AI system designed to automate a human job ends up needing an additional human to check the output, is it really saving resources? Will HITL just be a different kind of "resource" in the future? 🤔

Interesting interview!