Urban Technology at University of Michigan week 247

Are Smart Cities Trying to be Boring?

This week we ponder smart cities and why it seems like they are required to be boring and lifeless. If you’ve had other experiences in a smart city or district-scale project, please share with us as we would genuinely like to have more references in this area. In the meantime, let’s zoom to Shizuoka Prefecture in Japan and look at Toyota’s efforts there to build the city of the future.

💬 Hello! This is the newsletter of the Urban Technology program at University of Michigan, in which we explore the ways that data, connectivity, computation, and automation can be harnessed to nurture and improve urban life. If you’re new here, try this short video of current students describing urban technology in their own words or this 90 second explainer video.

🐴 Horses Make the City Smarter

The most interesting resident of Toyota’s Woven City is named Minnie and she loves carrots—probably. Minnie is a horse and, as the Chairman of Toyota Motor Corporation jokes in the announcement of Woven City’s first phase being completed, she is welcome in the prototype town because all transportation is intended to be zero carbon. I’d like to say “welcome to the weird world of urban tech development projects” but actually this world is not particularly weird, and that’s unfortunate. Here’s the video. Fast forward to 4:21 if you want to meet Minnie.

Projects like Woven City and the dozens more you will find itemized in Cornell Tech’s Atlas of Urban Tech are pretty much uniformly boring. The announcements, like this video by Toyoda-san, generally tout important but polite innovations such as the aforementioned zero carbon mobility or experiments in renewable energy. But for all the innovative spirit, building at the scale of a district or a small city quickly becomes a more mundane question of real estate economics. These developments are almost always underpinned by some kind of play to realize a higher and better use for unloved land. That’s certainly the case for Woven City, which is built on former factory grounds. In examples like Philly’s Schuylkill Yards, the development of a smart district is a play to attract innovative companies and their promise of high-wage jobs. These projects have the trappings of large, contemporary capital investments. The cafes all smell vaguely of Williamsburg, the parks are artfully asymmetrical, and you will almost certainly spot placemaking detritus like oversized Jenga or a corn hole set languishing in the public realm.

What’s odd about smart cities projects is how they almost always lack cultural specificity and go out of their way to hide or eliminate any quirks. It’s almost as if cities of the future are some bizarre mullet: innovation in the technology and employment ambitions but traditional values in the street and domestic life. Some, like Solano, go so far as to use watercolor-inspired renderings (a common technique to make development plans less scary to the public) and claim to be “building the city of yesterday.” Presumably they would agree with Shannon Mattern’s line that a City is not a Computer… but actually, computers can be really weird! Maybe smart cities actually do need to be more like computers.

If Woven City took a clue from the Gameboy Camera and Printer I’d be all over it. The Gameboy camera took something that had a singular use (games) and turned it into a culture-making implement. The Woven City version of that might be Toyota office buildings that become public access facilities like libraries, workshops, and cafeterias at night. Sorting out such a dual use would be crazy complicated if you wanted to preserve security of IP and other logistical considerations, but it would also make the experience of living in this company town quite unique.

The world of erstwhile laptops is riddled with things that are kind of insane, like the ThinkPad W700ds mobile workstation with its foldout second screen or the Acer Predator 21 X that has a detachable numeric keypad that can flip and become a trackpad. I’m guessing that both of these were commercial flops, but they are most certainly deep responses to some very specific set of behaviors and user needs. Whoever designed the Predator 21 X would totally get that Minnie needs watering troughs added to the Woven City so she feels can be a first-class citizen. It might have color changing LEDs and aggressive ventilation grills, but those much needed water troughs would be there because Minnie isn’t truly welcomed without them.

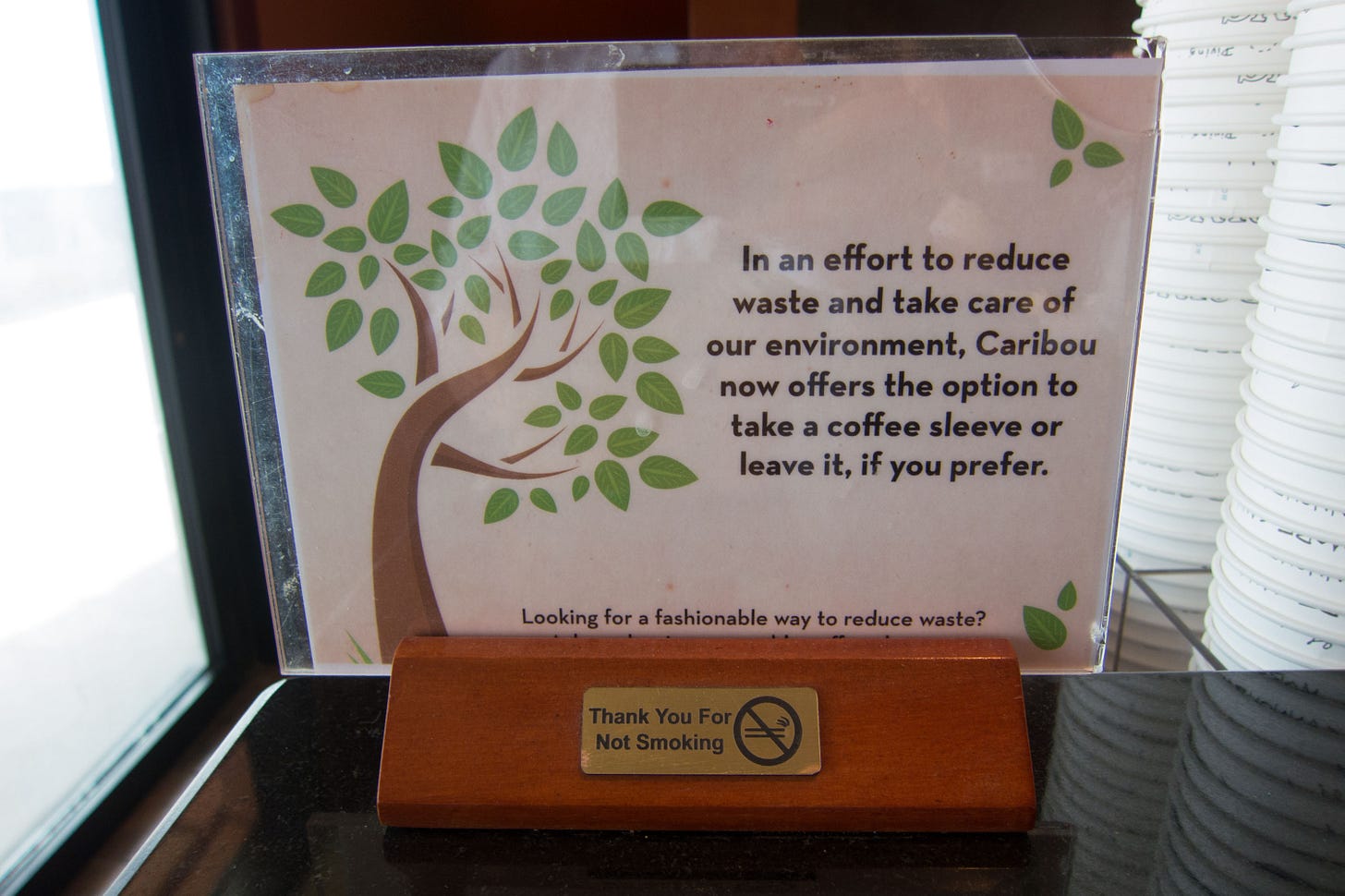

Masdar was the most talked about smart city of the early 2000s era and it promised to be a net zero community in the desert. To make this possible it required that showers be limited to a specific duration (see this report, page 23) which was, apparently, not shared with residents before they moved in. The failure to achieve their environmental targets was blamed, in part, on user unwillingness. By the time I visited in 2013 they had quietly downgraded their public statements about being net zero, but a local cafe was still giving it the college try and inviting people to skip the sleeve on their coffee to help save the environment. “A” for effort, I guess. Would they have been more successful with their carbon targets if the project had been more careful to attract people who are aligned around the same aspirations of living in harmony with Earth’s natural limits?

There’s a balance to be struck. If Masdar soft peddled the behavior change needed to make their project a success, the Honduran Crypto mecca Próspera went full tilt in the opposite direction. That city actively tried to court a global community of hyper-libertarian, hyper-macho crypto enthusiasts and the results are not looking so good. Between normcore cosplay and manosphere monoculture there exists some yet unrealized sweet spot of careful innovation. To borrow a line from my colleague Matthew Wizinsky, what would be a city designed around “social practices toward post-capitalist livelihoods” invite? Repair cafes, insane gardens, new rituals of mutual aid. They might have unique dining rituals or specific ways of getting the kids to and from school.

Woven City’s announcement video showcases the high quality, generic urbanism they are building. The architect of the project clearly paid close attention to Sidewalk Toronto because Toyota lifted the idea for Sidewalk’s street network that interlaces separate pathways for pedestrians, cyclists, and vehicles. But wait a second, which lane does Minnie use? And do little robots traverse her path to clean up the mess she leaves on the street? Embracing these questions would create some real innovation. And while those innovations may be irrelevant to many people, like the extreme laptops mentioned above, their pursuit would open the door to unexpected and emergent discoveries.

The important thing here is that a smart city inhabited by Toyota corporate employees and horses is a city of built-in differences: different diets, different paces, different mobility needs. The best cities help inhabitants navigate differences gracefully through careful handling of public space, sidewalks, avenues, edges, and overlaps. Earnestly designing for different forms of life would be a heck of a way to pull this need to the forefront. A smart city with horses would be a wildly different place indeed, and that’s exactly what’s needed to escape the twin traps of boring normcore urbanism and maximalist brotopia. Save us, Minnie!

A Trip Down Market Street 1906 × YOLO v4 Object Detection - an experiment from the quiet days of early COVID lockdowns by yours truly

These weeks: Congrats to Matthew on the successful dissertation defense today! 🏃