Urban Technology at University of Michigan week -08

It’s the end of the semester here at UM which means that students are abuzz presenting their final projects and we’ll show an example below. Before getting to that, let’s take an idea for a walk. It’s no secret that Michigan is the birthplace of the modern automotive industry, nor is it news to anyone that the global economy has shifted since the time of Henry Ford. There’s a renewed sense of innovation and competition in the automotive industry thanks to self-driving technology and electrification, and Michigan the state as well as Michigan the University will continue to be extremely active in building the future of the industry. But…. but…. we can’t help but wonder, what else might Michigan’s automative know-how be applied toward?

Hello! I’m Bryan Boyer, Director of the Urban Technology degree at University of Michigan that will welcome its first students in the 2021-2022 academic year. If you’re new here, try this 90 second video introduction. While we launch the program, we’re using this venue to explore themes and ideas related to our studies. Thanks for reading. Have questions about any of this? Hit reply and let us know.

🐖 What are the 150 byproducts of an F-150?

The Ford F-150 is a very popular truck and concrete evidence of a broad array of expertise, from the detailed engineering of every component to the establishment of financial access through loans and other mechanisms. To re-state that: cars can only exist because an entire system of invention, manufacturing, sales, maintenance, and fueling have been established around them. Sure, the F-150 is a marvel in many ways, but it’s also the show pony. The systems that enable the F-150 are 10x more impressive if you ask us! The question, then, is what else those systems can be used to produce?

Can the mechanical engineering expertise be re-purposed to help build locally manufactured bikes and e-bikes? Why not? Can the experience needed to build passenger vehicles be translated to designing small delivery bots and logistics services? For sure, and that’s already underway with local examples like Refraction AI, BrightDrop, and so many others. When you stay in the realm of mobility there are myriad direct translations.

Last week I visited Marrow, a local restaurant and butcher shop, where they have a butchery diagram on their wall showing the various cuts of meat that can be taken from a pig (sorry, veg folks) and it’s kinda wild to think about the difference between a pig and “pork.” The pig is simultaneously a whole and perfect creature as well as an aggregated collection of cuts of meat for meat-eating humans (bacon, chops, belly, etc).

An obvious statement, for sure, but what it inspired was a wandering thought about the 150 byproducts that could be “carved” out of a truck. If we conceptualize the vehicle as result of cumulative expertise and capability, how many alternative outcomes could be enabled instead of (or in addition to) the truck itself?

How would the “butchershop diagram” of a truck look and what would that visualization help us think of in terms of re-using expertise? What would you do with all of these various bits of know-how? How would you re-combine them?

Though the movement of people and things is hugely important, urban technology as a field is bigger than vehicles and mobility. We also need to think about housing, power, water, food, and all the rest of the stuff that makes up urban environments. Even if you wish cars were a much, much, much smaller part of everyday life (disclosure: I do), it would be foolish to not find a way to repurpose and recycle the existing know-how that exists within the many systems that make automobiles viable in American society—or global society, really.

Some good news is that expertise is expandable in ways that an animal carcass are not. When you make and consume a taco al pastor, the animal is gone and digested. But the expertise that exists within the automative world, and the new forms of expertise being strengthened right now around automation and electrification, can also be applied to adjacent industries. An auto exec applying their expertise in consumer financing to make it easier for individuals to access low-carbon heating and cooling systems for their home is cruelty free innovation. No industries or engineers need be harmed in the process!

How would the glass expertise used to create complex windshields be used to create homes that easily stay warm in winter?

How might the storytelling power of the automative marketing machine be used to mobilize people to support local food growing?

Could the ability to create a product that can be altered and repaired by owners and users become the basis of a new approach to furniture?

Might supply chain techniques from automotives help repair or build streets more effectively?

Can the robotic fabrication expertise needed to assemble a contemporary vehicle be used to fabricate low carbon homes?

🌲🪓 Forestry for the Commons

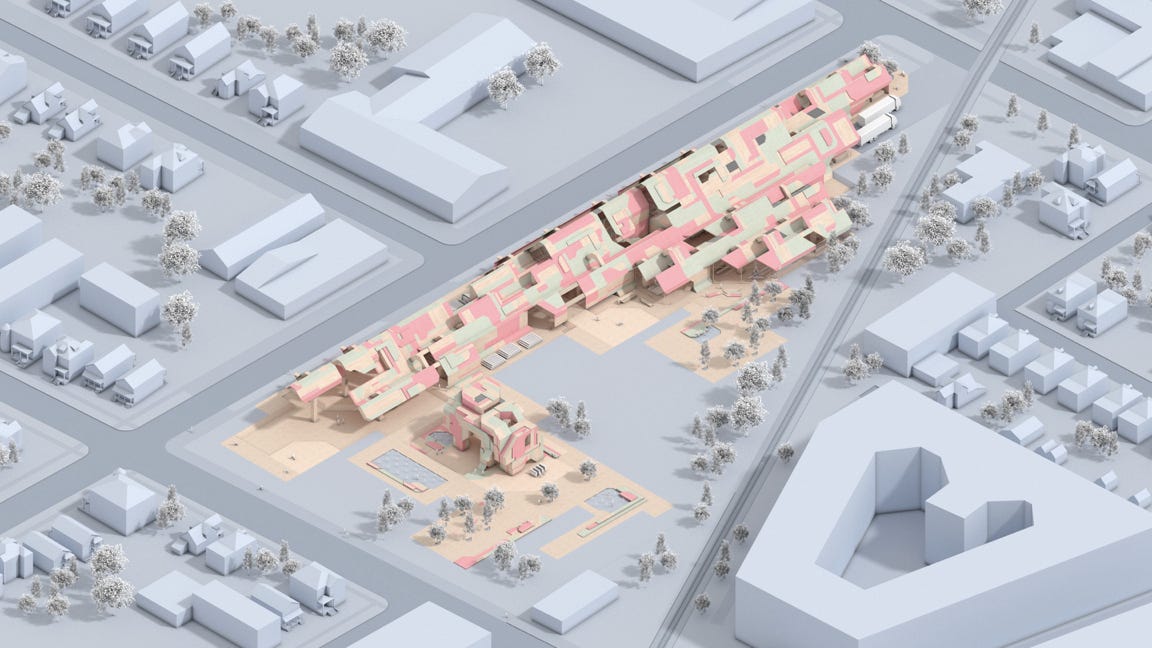

The last question above brings us to the work of Grant Parker, a Master of Architecture thesis student at Taubman College who was advised by Jose Sanchez, who you may remember. Parker’s project, Forestry for the Commons, imagines a Michigan-based, vertically integrated ecosystem of cross laminated timber construction. Let’s unpack.

Michigan-based. According to Parker, half the counties in the state have forested areas that are supportive of timber production. No surprise, really, since timber was an important industry for the early history of Michigan’s statehood. Rather than large swaths of land being owned or leased by single parties, Parker found, timber forests here are owned by myriad individuals. This creates a challenge in that no one owner of a patch of forest can provide much wood, but if everyone works together it could be a strong pool of natural resources.

Vertically integrated. The supply chain for the built environment is highly striated, meaning there are lots of different companies and parties involved even when building something simple. The person who sells you a 2x4 piece of lumber is unlikely to also own the forest it was harvested from, the mill that turned a log into your piece of lumber, nor will they be the contractor that builds your house. Instead, there’s a whole marketplace of materials, manufacturing, distribution, and retailing of goods and services. Everyone involved in this non-integrated supply chain have their own incentives and interests, and they often do not like having to change how they operate. Lots of inertia.

Long story short, if you want to be innovative in the built environment it’s easier to invent new widgets than it is to create a new approach to doing something like building a house. Not everything can be solved or addressed at the scale of a widget though, so if you truly do want to reinvent how a house is created, or you want to make houses radically cheaper or significantly less carbon intensive, then you want to have everything from the forest to the final product under your control so you make improvements across all aspects of that supply chain while having a lower cost of coordination. You spend zero time negotiating with suppliers, for instance, but in exchange you suddenly have a more capital intensive business, which means your business is more expensive and has higher risks.

Cross laminated timber (CLT). A new way to build buildings out of wood that is safe, assembled quickly, and creates pleasant interior environments. Even more importantly, because CLT is made out of wood, it sequesters CO2 for the duration of the buildings life, which is a significant leg up on alternatives like concrete. Since it uses wood and Michigan has so many forests, you would think that CLT is manufactured here already. Alas, it is not! Nor is it widely used in construction in the US. Michigan has just one CLT building currently (an area in which the Spartans currently have us beat) and in the US as a whole the numbers are also quote low but growing, thankfully, as the technology is being imported from Europe and Canada.

You might think of CLT as producing futuristic log cabins cut by robots. Based on this description, you can probably tell that CLT is a very different approach that balloon framing which is commonly used in North America.

Based on all of that, a Michigan-located, vertically-integrated CLT company sounds pretty cool, but if you read carefully above you noticed that the makeup of land ownership in the state creates a unique challenge. How do you get a bunch of people who own say 10-50 acres of forest to collaborate? Perhaps, Parker imagines, by forming a CLT cooperative.

A bunch of small-hold land owners might band together to create their own supply of natural resources (🌲🌲🌲) which are then utilized in a network of factories (🕸🏭) across the state of Michigan (🧤) to fabricate building materials and components, and ultimately to enable the next generation of homes, schools, offices, and workplaces (🔮). What could better buildings mean to the state of Michigan?

More energy efficient = lower carbon footprint, lower operations costs, and higher levels of human comfort. Quicker to build = cheaper, less disruptive to neighbors, and more opportunities for add-on innovations. Locally manufactured = a source of massive opportunity, more local jobs, and results in a critical feedback loop of pride: when people make what they need, they also need what what they make.

Parker will graduate this weekend with a Masters of Architecture degree, but these questions are exactly the kind of things that matter to us in urban technology. We care about the systems and services that enable us to see, shape, and inhabit the built environment in new ways. And personally, the world Parker imagines is one in which I would happily live.

So let’s ask again, what know-how could be repurposed from Michigan’s immense expertise in the automotive realm to produce something like the CLT factory and learning center seen in Parker’s thesis project below?

Links

🚂 In honor of Grant Parker’s final review sparking discussion about train lines and their use (or disuse), here’s a visually lush overview of schematic railway maps.

🪨 3D printed buildings get lots of headlines but look how mundane this is! I’m speaking with Arash Adel soon and wondering what kind of house his robots would build. h/t Anthony Townsend

🤖 What if instead of building architecture, robots reorganized it for you? From a nice thread from Kat Dov on rethinking interactions with buildings.

🪜 OK but what if the building components could move too? Here’s a project from the UK that proposes reconfigurable elements to enable not just self-provisioning of spaces, but the ability to tweak and adjust those spaces (without a robot).

🚧 We live in a world where Mr. (Traffic) Barricade has nearly 400k followers on TikTok for narrating his cycling infrastructure tweaks and reader, let me tell you, this is one small glimmer of hope.

This week: Final reviews: lots of them. Awesome work by lots of students. Numerous discussions with prospective students running up to the decision deadline which is… tomorrow! Engaged with the Business Engagement Center. Made plans to speak with urban planners. Spent a lovely hour with Alex McDowell who you may know from his work on world-building for feature films. Need to start developing some meters to help us keep a sense of the pace here. Was this a particularly busy week or did it just feel like that? 🏃♂️