Urban Technology at University of Michigan week 140

Design Fiction and "Imagining Harder" with Julian Bleecker

Recently we enjoyed hosting Julian Bleecker for an afternoon at University of Michigan. Below we’re including a version of the talk he gave at Taubman College, edited lightly to sing in your inbox as it sang in our lecture hall. If you don’t know Julian and his work, scan the italicized intro below and I suspect you’ll quickly find reason to stick around and read his full talk.

💬 Hello! This is the newsletter of the Urban Technology program at University of Michigan, in which we explore the ways that data, connectivity, computation, and automation can be harnessed to nurture and improve human life in cities. If you’re new here, try this short video of current students describing urban technology in their own words.

🧠 It’s Time to Imagine Harder

Julian Bleecker is a Los Angeleno, a designer, an engineer, an entrepreneur, a writer, a cyclist, an author, a careful thinker… and that means he is also a symptom of an era whose issues do not fit neatly into the boxes of our grandparents' world. He once described his work as creating “symptoms of a future world." As his PhD advisor—the legendary Donna Harraway—might say, the diversity of Julian's work is an example of “staying with the trouble.” From being cofounder of Near Future Laboratory, creating the company OMATA, to being part of the legendary Nokia design term, Julian’s career is a series of experiments in how seemingly simple things, well designed, can complicate the world around them.

Julian is also a cause. His concept of design fiction has inspired countless folks—including me—to make up worlds by making up things. At a time where entire new cities are proposed and visualized every few months, futures blossom like Viennese Gesamkunstwerk: seductive, seamless, and perfect to the point of suffocation.

Design fiction is the opposite. Instead of grand narratives, design fictions are purposefully small and episodic. Instead of complete ideas, design fictions are undone and partial. Instead of clear, design fiction is foggy in ways that create room for genuine speculation. To extend that metaphor…. Picture yourself standing outside looking toward the horizon. A thick fog has set in and it blurs the line of earth meeting sky. No matter how much you squint it’s impossible to make sense of what’s ahead, and yet difficult not to wonder what lurks beyond the point of perception. Here in the fog, when vision fails us, we have no choice but to imagine harder.

Transcript edited and condensed:

I started thinking about this phrase (below) that kept banging around in my head, which was the relationship between creative consciousness and what I've taken to call “Structure.” There is always this predicament where creative consciousness needs to contend with Structure. The form of that is: I've got an idea and I wish I had a studio where I could do my thing. I wish I could just let my Imagination run free. But at some point, someone's going to say, “Hey, can you pitch your idea?” and as soon as they say that, Structure has entered the room. The first thing that's going to pop into your head is a PowerPoint.

Now you have to contain your Imagination in 16:9 aspect ratio slides, and be ready to share 11 slides in 20 minutes. That's you entering the jiu jitsu match with Structure. This is you contending with Structure — the experience you have to go through in order to articulate the beautiful idea that came to you one day while you were in the shower or while you were walking, thinking “I wonder what that's about…” “I feel something…” or “If I had my way it would look like this.” And you're trying to translate that feeling that you had – which is just a feeling, pre-language – into a form that becomes legible to Structure, to the PowerPoint, 16:9, etc.

You're trying to find the vernacular that's going to resonate, because you know you need Structure – it would be nice to have a budget, or to get paid for my time. I've got all this value; how do I translate that into a form that is going to feel true to the feeling I initially had, and that also gets Structure to sense the value of it, when Structure goes, “yeah, actually, we need that!” And you’ll say, Wow, someone needs me. This is awesome. They're gonna give me a budget! Now it's feeling right, like the relationship is right.

It occurs to me that when Imagination and Structure are in harmony, when they're collaborating, beautiful experiences are attained. We get things like this:

For me [the photo shows] a moment when Imagination and Structure are in deep collaboration, when someone's like, “I think we can get a guy floating up in space.” And people go, What are you talking about? That's crazy. Where did that idea come from? Are you insane? “Maybe I am. But I think if we follow along this path, something like this will happen.” And the magnitude of the Imagination and creative consciousness that can come to enroll half a million people to hand build a spacecraft, and a spacesuit, and all the other things in order to create this moment — it's beautiful. I find it heartening to realize what Imagination and Structure can do in collaboration. It's like, if we can do this, name another problem and let's go after it. And let's do it in that same spirit, with Imagination and Structure in deep collaboration, one feeding off the other in this beautiful exchange of value and meaning.

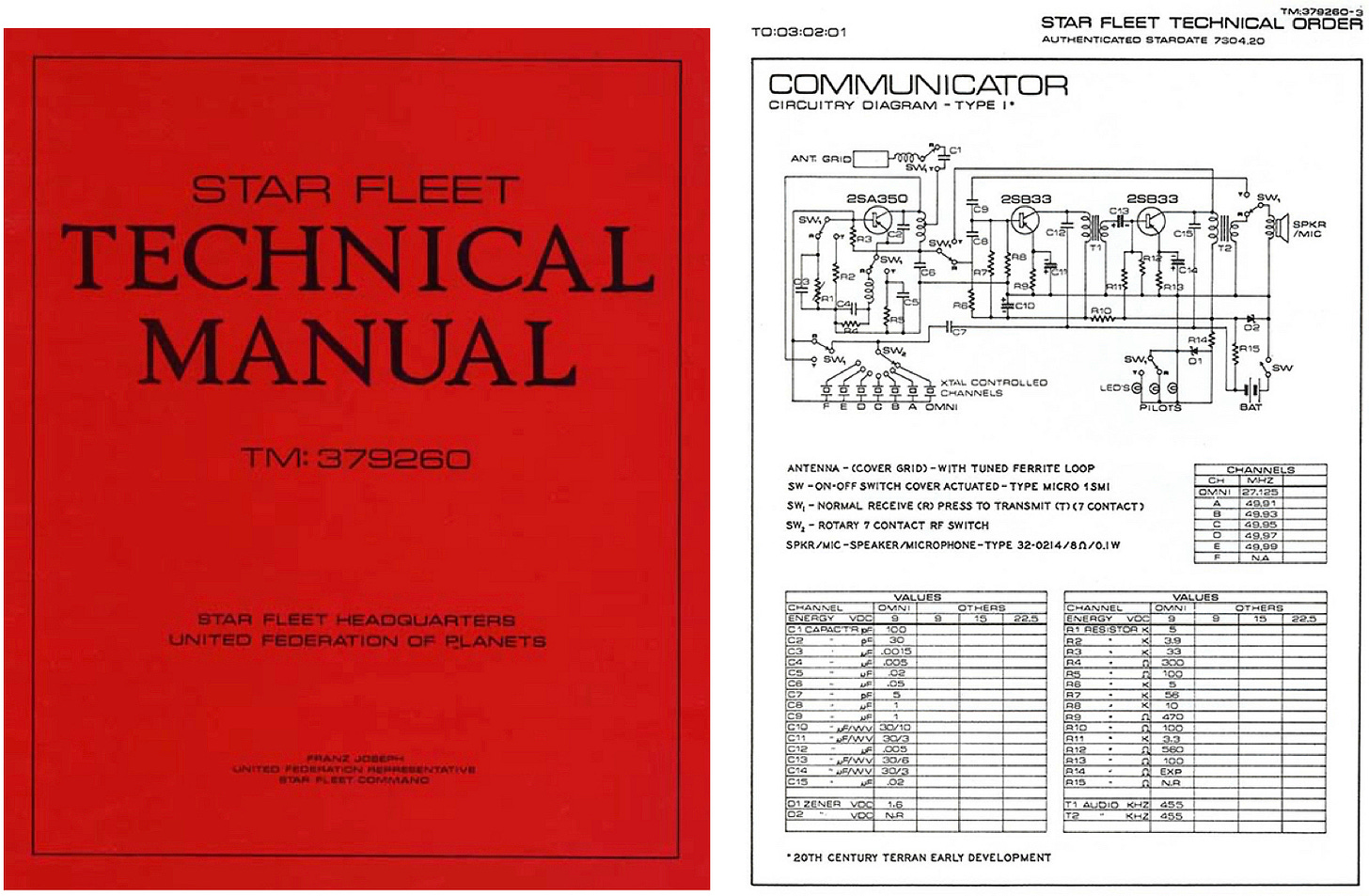

Growing up I was definitely a Star Trek fan, and at some point my dad took me to a Star Trek convention in New York. I was walking around the tradeshow looking at stuff, seeing what I could get, maybe a t-shirt or something, and I came across the Star Fleet Technical Manual:

I was like, Whoa, what do you mean? Technical manual? I don't get it. It's a show. How could there be a technical manual for the show? I started flipping through it, and that “whoa, cool” feeling went to level 11. I didn't know what was going on. How is it – and where did this come from – that there's this technical manual that represents the fiction of the world as a thing that exists, that is actual. That even gets to the level of an electrical schematic. I’d been playing around with electronics enough at this point, with kits and that kind of thing, that this actually had legibility to it. Oh, this is right. Look, there's a speaker, three transistors, I know this kind of circuit. I've seen this before. Oh, there's a battery.

This is a real thing.

What's going on here?

I imagine just looking at this book, and then looking at the guy selling it, then looking at this book, looking at the guy, like, “Where'd you come from? Where did you bring this from? How did you get this back in time?” It was just a wonderful, beautiful sense that something else is going on here or that there's another register to this universe that I've never seen before. And look! I can pick it up. It's printed and bound. It's a real thing.

Then I think, where does something like this come from? Where did things like this get made? It's very distant from where things are made when you think about the television show. There, there’s a studio, there's a film lot, there's someone who yells “action” and “cut.” That's a different mode of coming into existence compared to something like this.

It turns out the Star Trek Star Fleet Technical Manual was made by a guy named Franz Joseph. He was a mechanical draftsman for a company called General Dynamics in the 1960s, probably doing aerospace stuff. He had this kind of Imagination about Star Trek, being a fan, that drove him to translate his imaginary of that world through the tools, techniques, and practices that he understood and did day in and day out, which was in the form of these diagrams - the kinds of diagrams that are legible to Structure. And he just went a little bit off the hook. Right?

No one was asking him to do it. No one from Paramount, which produced Star Trek, said, “Hey, could you do this for us?” He just did it on his own. Why would someone do this? What was it that drove them? This was my question. This is basically a brand book for a fictional world that someone just decided to sit and spend their days doing. Unexpectedly, it became a bestseller, and 46 years later it's still in print. So what is going on here? Why is there this relationship between this idea of a technical manual and a fictional world? What drives us to be tickled by it, or inspired, or spend real money on it?

If we want to understand what Franz Joseph is doing, there's a kernel of a practice there that I think we really need to tap into at this particular moment in the evolution of humanity. We've got some real problems that we need to address, and it feels to me that the way we've been addressing them isn't quite working. It's not that beautiful harmony of creative consciousness with Structure, with our ability to imagine into worlds while working with the institutions (organizations, companies, whatever it is) that have the capacity to actually materialize the things we imagine. In my view, Franz Josef has inadvertently and indirectly reminded us of the ways in which you can take creative consciousness and make it legible to Structure. Where the Structure goes, “Okay, I see it. Now I get what you're saying.”

When I look back on what I’ve been developing, design fiction feels into that, in a way. My latest approach is to look at what archaeologists do. Archaeologists dig into the past, right? They dig into the ground looking into the past. They're looking for representations of worlds that were, and they have no one to talk to, because the people who could have given an accounting of what happened are gone. So they find a fragment, and they look at it intensely. They ponder it. They're asking it to tell a story. What were you? What did you come from? Are you a fragment of bone? Are you a trophy from a war? Are you a totem for a god? What was your god? Does that have something to do with that weird Structure over there? They're trying to translate what that world was like through a material artifact. That's all they really have. For them, the past is these objects that contain the experience of that culture—the hopes, dreams, fears, desires, ambitions, and the nature of that world.

What design fiction does, as I've learned from Franz Joseph, is that we can dig into the future in the inverse of the way an archaeologist does. And rather than telling master narratives of what the world will be, we just look at it in this partial way, with a certain sense of humility. I can't predict the future. I just want to help us ‘feel into’ that world and represent that world through some things that I found, these artifacts, these speculative objects.

Design fiction can be captured in that sense: the creation of tangible prototypes of the material cultural artifacts of possible near futures.

The point of doing it this way is to bring Imagination into the conversation, and then represent what your Imagination feels into, the shape of the world, not as a master narrative or even as a prose-based story, but through objects. And these objects are essentially things that people can gather around and wonder into. You may not even have a complete story about the object. What you want to get to is a place where people ask questions. You want them to say, “Tell me more about this.” And then you start that conversation. Design fiction creates those kinds of evocative objects, like that communicator schematic.

In a practical sense, if we think about the ways we do futures work, the typical way is a futures report. If you're commissioned to give me an analysis of the future of food, your first instinct is probably going to be gathering a bunch of source material on the future of food, which today usually means going to Google or maybe ChatGPT and asking it to tell us about the future of food. You gather a bunch of this material, categorize it, index it, and identify different aspects of whatever the future food might be. And then what do you do? You create another report that's a synthesis of all this material. In fact, Structure might have already told you this ahead of time: We're going to be presenting to the board, so it needs to be a PowerPoint, probably 11 slides, 16:9… So you’re already expecting what the result will look like.

But imagine if instead of that PowerPoint, you have the freedom or flexibility to say, “I don't want you to tell me how I'm going to present it, I'll take care of that. It's going to be beautiful.” And in the back of your mind you're thinking, I'm going to give them a box of cereal from the future. I'll tell them I have a crappy time machine behind my studio. It smells like sweat and machine oil. There's a big button on it that says DO NOT TOUCH EVER. There's a lever that has a repair tag on it that says, Please fix as soon as possible. But it's dated a few years back. The little dial you adjust to pick what time and place you want to visit is swinging free like a broken faucet. And the button that says DO NOT TOUCH EVER, you're like, I gotta hit it. You hit that button, and you end up in someone's breakfast nook. You look around and grab a couple of things because the machine seems like it might go back at any moment. You don't have a lot of time. You don't get to talk to any major politicians, decision makers, legislatures; you don't even have time to do a bunch of user surveys. You just have time to grab a couple of artifacts. Remember, you're the inverse of that archaeologist. The archaeologist doesn't get to talk to anyone. They have to surmise what the world might feel like.

So you grab this box of cereal and get back in the time machine:

What's going on with that box of cereal? Does it tell us something about that world?

What you've done is translate some of the research that you gathered. Maybe some of the research said that in the future, insect protein will be a major source of protein in the human diet. Rather than saying that, you went ahead and designed the packaging for a box of cereal that represents a translation of all that research in a tangible form. You're doing a little bit of a Franz Joseph, saying, I'm not going to tell you about the world – I'm going to represent it as an artifact, as if I went to that world and brought it back. And when you go to that boardroom, you plop down that box of cereal and say, “I'm done. This is what I found.” In that translation, you’ve brought your Imagination straight to Structure, because Structure gets the things that you show it. They get a box of cereal, they get a drink that has their company branding on it. And you get them to engage in a conversation around this topic. Maybe that old-fashioned futures report is still there alongside it or as an appendix, but you are saying, I'm going to bring you my Imagination in this other form.

In another project, a large autonomous vehicle company asked us to do some work on the future of autonomous vehicles. What we did was create a magazine from their future, in collaboration with them:

We listened to their fears, hopes, dreams, desires, their concerns – the kinds of things that often don't get included in a futures report, because futures reports are all up and to the right: “It's going to be spectacular, amazing, here are the revenue projections, here's what the world is going to look like.” In a container like a magazine, you can tell so many richer stories about the future. There's a letters to the editor section complaining about how many manual drivers are still on the road. There’s an article about issues with the new certifications you need to operate an autonomous vehicle. There’s an ad for a Museum of Manual Driving, where kids can try a K-turn like their grandpa used to do. Hey kids, ever wonder how it was like to parallel park without a robot doing it? And so you can express these things and allow people to feel into the future in a way they wouldn’t otherwise.

That's design fiction. Aside from the practical aspects of it, as described in The Manual, I think we need to find better ways of bringing Imagination and Structure into close collaboration. Different ways of sensemaking and seeing and feeling into possible futures are needed, ways that engage people and, without diminishing the importance of the work we do, have a certain lightness to it, a sense of wonder. That hopefully make people smile or have a light chuckle. It shouldn’t diminish the importance of the work. We can be serious, and we can also be engaging and creative and imaginative, and look at the world in a slightly different way.

🎤 One question for “Julian Bleecker”

Since we forgot to ask Julian The One Question We Always Ask Our Guests while he was with us, I summoned “Julian Bleecker” via Chat GPT for a quick interview.

Bryan: What is your favorite city and why?

Chat GPT answering in the voice of Julian: As Julian Bleecker, it's difficult for me to choose just one favorite city, as I find inspiration and fascination in so many different urban environments. However, if I had to narrow it down to a few, I would say that Los Angeles, Tokyo, Berlin, and Helsinki are among my favorites for different reasons.

Los Angeles, where I currently reside, is a city that is constantly evolving and reinventing itself. It's a place where people come to pursue their dreams, and the result is a diverse and dynamic culture that is always pushing the boundaries. Plus, the weather is great and there's always something new and interesting to discover.

Tokyo is a city that I find endlessly fascinating for its mix of tradition and innovation. The attention to detail in every aspect of life, from food to fashion to architecture, is truly remarkable. And the way that the city seamlessly blends the old with the new creates a unique and compelling atmosphere.

Berlin is a city that has undergone a remarkable transformation in the years since the fall of the Berlin Wall. It's a place where history and creativity intersect in unexpected ways, and the energy of the city is palpable. There's a vibrant arts and culture scene, and the city's rich history is always present, making it a fascinating place to explore.

Finally, Helsinki is a city that holds a special place in my heart. I spent a significant amount of time living and working there, and I was always impressed by the city's focus on design and innovation. The city is surrounded by beautiful natural landscapes, and the architecture and design of the city itself is truly inspiring. Plus, the Finnish people are incredibly friendly and welcoming, which made my time there all the more enjoyable.

These weeks: Admitted student events are happening so it’s a special time of year where potential energy is through the roof. And it’s good that this is the case, because most of the day every day is a crush of logistics for our cities intensive semester kicking off in a few weeks. Little bit of hiring. Dreaming up Special Projects. The week got away from us so this is arriving as a special weekend edition. Happy Saturday, friends. 🏃