Urban Technology at University of Michigan week 133

Our First Design Studio + interview with Elisa Ngan

Ever find yourself staring at a progress bar wondering when it’s going to tick forward and why it’s not moving if, seemingly just a second ago, it was zooming toward the finish line? That’s one way to approximate the feeling of being 133 weeks into launching a new 4-year degree. There are 8 semesters of coursework to be created and we’re in the middle of semester 4, right at halfway. Of the 14 new courses that we anticipate building (10 required and 4 or more electives), we’ve developed and offered 6 so far. That puts us 50% of the way to completion by the calendar and 42% by the course count.

To celebrate the launch of our first design studio that’s been created from scratch for the urban technology degree program, I sat down with Elisa Ngan, who has developed and is teaching the course. By the way, if "studio" doesn't resonate as a term, it's what designers call project-based, hands-on courses. After the interview we zoom out to situate this studio in our broader thinking about design.

💬 Hello! This is the newsletter of the Urban Technology program at University of Michigan, in which we explore the ways that technology can be harnessed to nurture and improve urban life. If you’re new here, try this short video of current students describing urban technology in their own words.

🔬 Interview with Elisa Ngan

The practice of Elisa Ngan spans architecture and urban technology. At global architecture firm HOK she worked on projects including the Seattle Arena and AT&T Center in San Antonio, as well as a number of educational facilities. On the digital side, she has worked at SeatGeek, eBay, Treasure Data, and Tulip Interfaces as a designer and product manager, and in government as a design fellow at US Citizenship and Immigration Services. Elisa brings her precise, gregarious, and deeply reflective perspective on design and data to the urban technology program as our first (!) Professor of Practice in Urban Technology and is currently teaching our first (!) design studio.

BRYAN BOYER: Can you please tell me about the path you’ve carved for your career and studies?

ELISA NGAN: In a linear fashion – I got my B.A. in architecture from Berkeley, with a minor in city and regional planning as well as environmental design and urbanism in developing countries. I always thought that urban planning problems were more interesting but I also liked the rigor of the studio… I also wanted to be a branding strategist because it seemed more possible than architecture at the time. I ended up finding a great fit in stadia architecture which blended the branding, architecture, and urban planning, but I was also working in San Francisco where tech was a big part of the city’s culture and economy. We briefly talked about some of the consequences of tech in school, so I thought: “Why would I stay in architecture, when I can make use of the tech companies around me?” So I left and worked at a data management company called Treasure Data. That [was where I learned how to] work with a team to create a data engineering, data analysis, and machine learning platform.

When I applied to Harvard’s new Design Engineering program, my statement of purpose was about how the people who are building the technology we use everyday aren't trained to think about the environmental, social, and intellectual sustainability of what they are doing. Products are being designed to affect the way we see and understand things without thinking of the broader consequences. The negativity has really taken off since then, but I am still positive about the potential of technology to bring about a better world. We need to stop thinking about it from a place of fear, because fear never produces anything worthwhile. I play offense.

BRYAN: You mentioned that you thought you would go into brand strategy. Why was that interesting to you?

ELISA: I was in school in 2009, during the Great Recession. When I was scrolling on Facebook I saw: “What's the worst major you could have right now in the middle of this housing bubble? Architecture!” I always thought that you go to college to get a job, so that’s what I was focused on doing. I started looking into design strategy because there was a professor, Clark Kellogg, who was teaching design strategy to architecture students at the time. He was a former architect himself who went into design consultancy, and became my mentor in my last year at Berkeley. He made it possible for me to imagine a way of designing that wasn’t architectural but organizational.

I had also been working on graphic design for a really long time, probably since I was around 12 or 13. My parents are small business owners and I was always making all of their stuff. I thought I would love to go into branding strategy or design thinking because it made more economic sense than architecture.

BRYAN: Let's talk about the studio that you’re teaching right now, our first studio! What are the students doing in that course?

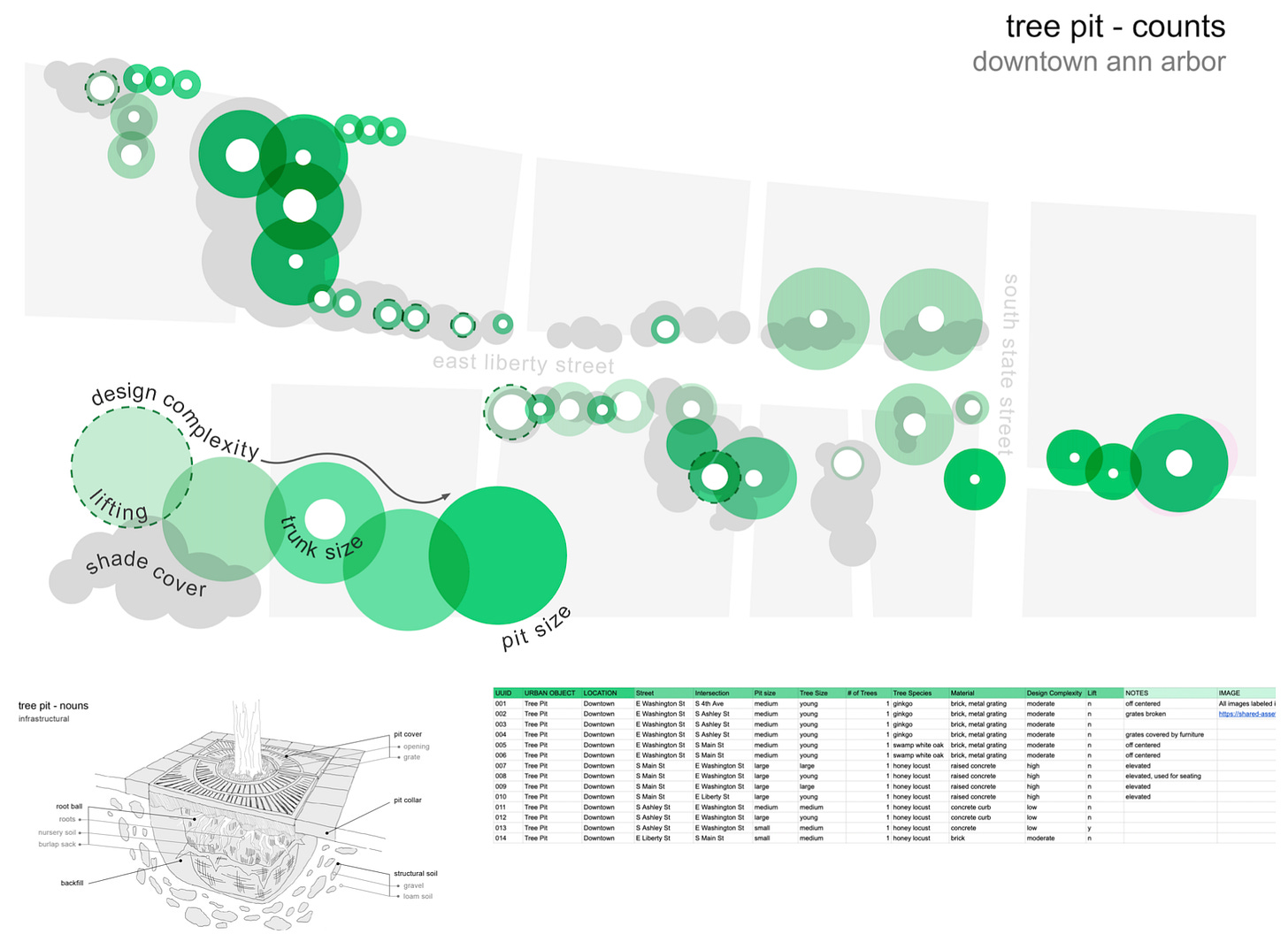

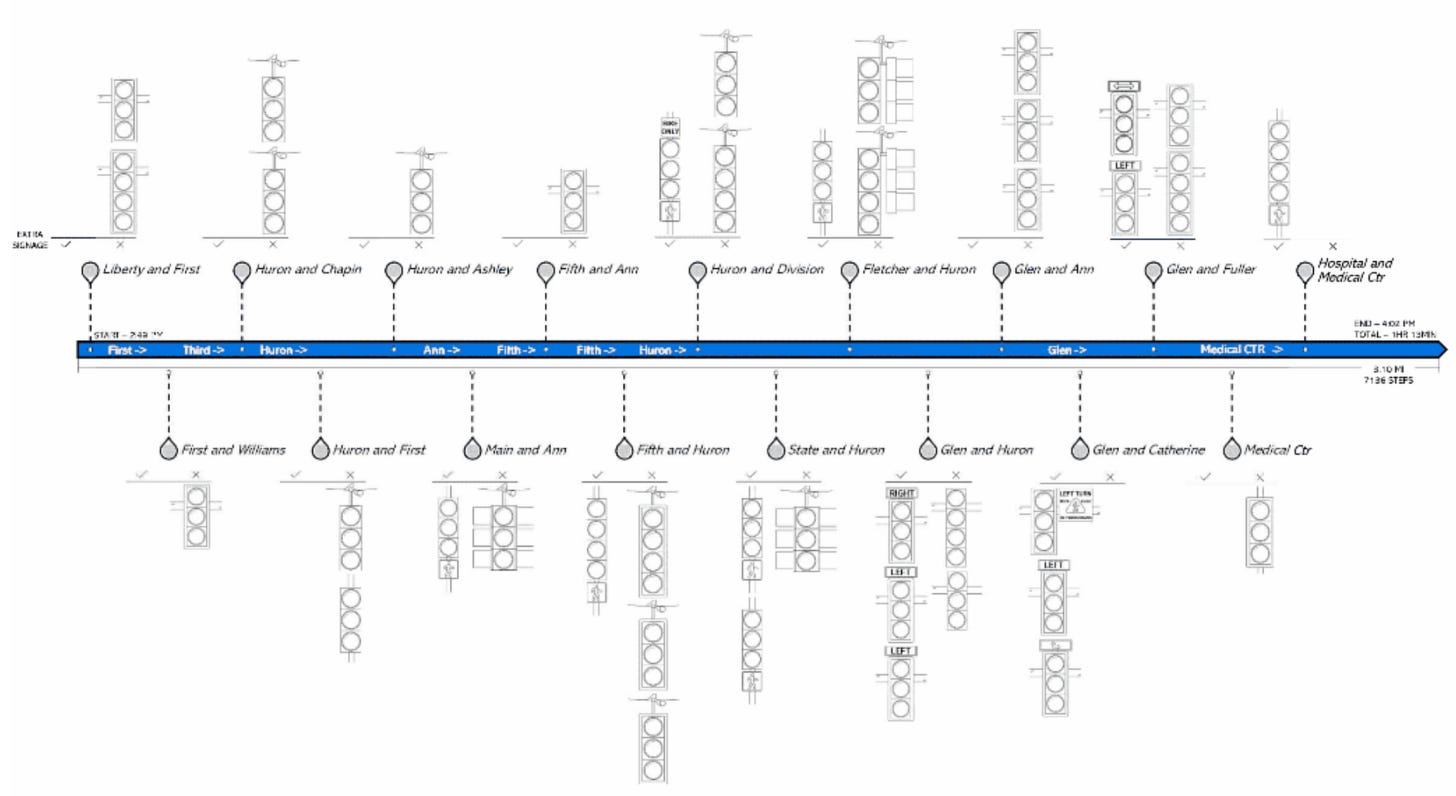

ELISA: The class is supposed to teach them about asking good questions, and they do that by obsessing over an ‘urban object’ of their choosing. Something like a street light or signage that shows up all over the public realm. I think it’s really important to be specific when designing technology, so one of the principles I have going into this class is to teach students to see with detail — both in terms of the physical object and the information side or representation of that object.

In terms of artifacts, what they’re doing is learning how to draw a representation of a physical object of their choice that exists in a public setting, and they’re learning how to create tables that also describe that object. They iterate both on the drawing side and on the table side. The table is an example of a data structure that you may work with when designing a piece of technology.

Even though they’re creating tables, they’re more concerned with the structure than the values, the assumption being that when you deploy a piece of technology the values come from the user. The designer’s job is to think about the structure of what could be collected, what things are missing within that structure, and the organization of that structure itself.

BRYAN: I look at a fire hydrant and I draw a fire hydrant as well as I can. Then I look at ‘fire hydrant-ness’ and I make a table to capture or describe that quality. Why is this ballet between the abstract and the concrete important?

ELISA: I don't think that one of them is abstract and one is concrete. I think both of them are very concrete. Actually, as we progress, we make them more abstract in the sense that we generalize our understanding of the object by looking at more and more examples, and it becomes an abstraction over time as the table stretches to include the facets of all of the instances of fire hydrants that we examine. But an abstraction, even though it has the word “abstract” in it, is still concrete. A technical system is a concrete thing, it's very literal, and it has to be so.

BRYAN: When you say that you're working towards becoming more abstract over time, why? What's the value of doing that?

ELISA: [It’s how we’re learning to build models of the world] that can encapsulate all of the context that has been discovered at the beginning. At the beginning of the course students went out into the world and took actual pictures of all of the variations, or instances we might say, of this idea of a fire hydrant that they have—this type of object called the fire hydrant. When the students have 20 to 30 pictures of them, then they can start building an abstraction, where one abstraction, whether it's in a drawing or a table form, should be able to describe the object photographed in each one of those 30 pictures.

BRYAN: What happens when a student finds some detail of a fire hydrant that seems unusual?

ELISA: That’s where we start to get really interesting conversations on outliers, because the natural inclination is to want to throw away the ones that don't fit the existing table that you have created. And my answer to that is, “No, you should work on your abstraction to include this example too. It is an anomaly you found, and what makes it interesting is that the anomalies tell you the most about the human side of the design.” For example, when we were talking about traffic cones with one student, she wanted to throw out the photograph she took of one that was on a roof. I told her to keep it and later our conversation became about the transgression of these cones as objects of control. That was a fun conversation.

BRYAN: What is your favorite city and why?

ELISA: I don't have a favorite city, but if I must give an answer I’ll say Berkeley. I lived there—I think it's hard, because how could you say you like a city you haven't lived in? One thing that would be uncommon knowledge to someone who hasn’t lived in Berkeley is that it has a lot of pizza. There is so much pizza in Berkeley. All types of different pizza, from $1 pizza to $25 pizza. There's a pizza place on every block. Probably because of the produce in California, so it's easy to make good pizza. I feel that it is such a pizza-oriented city, but in a soft way. When you open your eyes and see with detail you realize there are so many different pizza shops.

🍕 Curriculum Notes

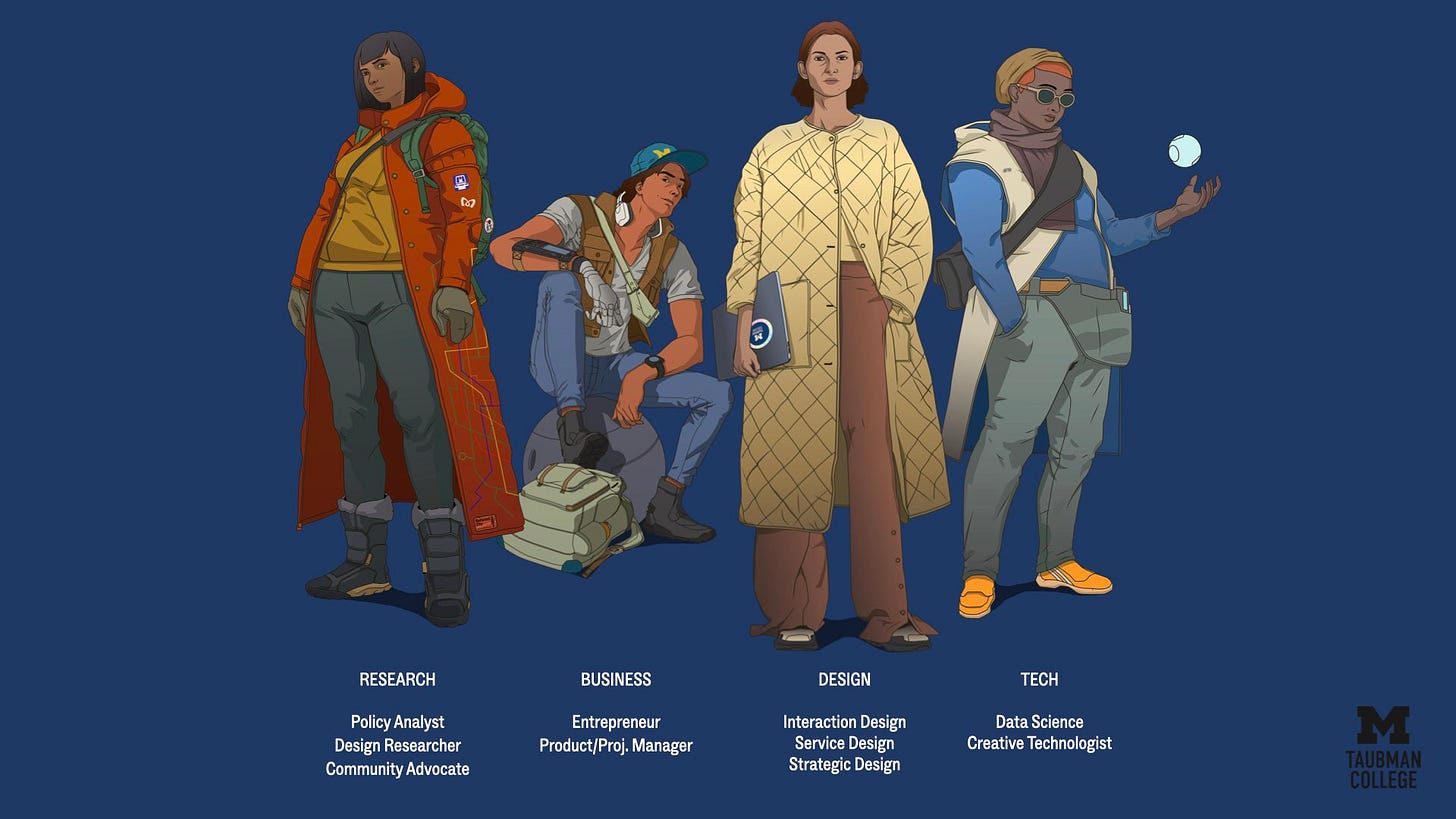

Our curriculum is organized around three sequences: cites, technology, and design. The latter is where some of our biggest bets are being placed. We're taking a transdisciplinary approach to the meaning of "design"—in other words we're not stacking up multiple studios in interaction design and asking students to stretch the definition, but instead are exposing students to a range of ways that design is applied and utilized in the context of urban technology. This makes executing the curriculum more complicated but, we believe, the learning outcomes will also be more robust.

Students will have four semesters of exposure to the design process and will walk away with four or more projects that they have worked on as portfolio pieces. During this sequence, each studio asks them to assume one of four different but related perspectives. Provisionally, those are:

Researcher role: Design and Urban Inquiries Studio

Designer role: Interaction Design and Urban Experiences Studio

Product Owner role: Service Design and Urban Needs Studio

Change-Maker: Strategic Design and Urban Systems Studio

The roles are cumulative across the sequence. By the final studio, students are researching, designing, and conceptualizing a product, and describing the role of that product in a larger arc of societal or environmental transition.

Below I’m clipping an image of the “crib sheet” from our design sequence overview that functions as a master requirements document. Across the top you’ll see columns for each studio course, and down the left column are a series of facets that describe the courses. The twenty or so rows of this table are the most compact way we have to define the individual studios and their relationship to each other. When Elisa began at Taubman College we looked at this sheet together, and almost immediately she proposed adding a row for “roles.” Brilliant.

Articulating a sequence of roles that the students embody with each design studio is important because we don't assume everyone will walk away from this experience and pursue a career in design. It’s fine if they do, naturally, but I also want the future CEO that comes out of this program to believe that innovation happens by design, and I want the future policymaker alum to think, "Of course a good research process should involve qualitative and quantitative perspectives."

Design will certainly be part of the students’ professional toolbox whether or not it’s part of their professional identity. Here's how we describe the spread of likely career trajectories (or graduate school) to prospective students and their parents:

In about 115 weeks’ time, we will reach a significant milestone: the graduation of our first cohort. While it may be a pretty safe bet that this illustration may change by the time we reach that date, it’s a sure bet that it will change once our first students enter the job market.

These weeks: The admissions prep call for faculty and staff reviewers makes it real. Prior years we took bets on the final results, but this year we’ve built a funnel and are dialing things in. Getting specific. Also: making notebooks and stickers, working on curriculum and syllabi for next semester, getting excited about Cities Intensive. 🏃