Urban Technology at University of Michigan week 188

Changing at the "speed of services" vs. the "speed of buildings"

Hello from Oslo. I spent the day here with Einar Sneve Martinussen from AHO, the architecture and design school in Oslo, touring around the university and the city. Thank you, Einar!

My mission on this trip was to learn from Einar and his AHO colleagues how they teach at the confluence of interaction design, service design, and the built environment. As anticipated, it was educational and thought provoking—truly inspiring to see what they’re working on, and have been working on for years, with elegance and humility. The day long tour through local social infrastructure, design studios, and the university was also a dense thicket of discussion threads so, rather than try to give a full recap, the body of this update is the story of a visit to a two-person design studio tucked away in the scenic grounds of the Edvard Munch Museum’s former home. It’s a story about the power of tiny software.

💬 Hello! This is the newsletter of the Urban Technology program at University of Michigan, in which we explore the ways that data, connectivity, computation, and automation can be harnessed to nurture and improve urban life. If you’re new here, try this short video of current students describing urban technology in their own words or this 90 second explainer video.

🤝 A Democracy of Small Apps Loosely Joined

Drive around Detroit in the summer and you’ll notice church steeples poking through the tree canopy in neighborhoods around the city at a quantity that would make you think Detroit is the most religious place on earth. There are about twice the number of steeples you might expect in a city of this size, built when Detroit was built. The churches are a marker of Detroit’s high water population of nearly two million in the 1950s.

Norway’s smaller towns are experiencing something similar. As young people increasingly move to Oslo and other major cities, the countryside is thinning out from a population perspective. A decline in population results in abundance in the built environment by virtue of fewer people to use the same schools, town halls, playing fields, and other urban spaces built for the peak population of those smaller cities. For instance, when two small towns consolidate under one municipal government, what happens to the town hall that gets deprecated?

Even if population doesn’t grow, needs change, so fallow spaces become a stage for reimagination. Whereas Detroit has the leftover buildings, it struggles to find the funds to reinvigorate them; Norway’s lucky to have relative abundance of both coffers and spaces. When left over spaces are emptied, who decides what those spaces will become? Which professionals are engaged to do the work of reimagination?

A tiny design studio in Oslo provides a glimpse of the answer. Travers is a studio of two alumni from AHO - specializing in design for “community development.” They make tools that let small cities collect feedback from the public. Or, I should say, they make beautiful, bespoke, and purposefully tiny tools, which is a refreshing alternative to the all-encompassing impulse that’s more typical of American approaches to technology. Rather than building a platform that solves lots of problems for lots of people and can be used (and sold to) any city anywhere, the tools Travers builds are one-offs that are pointed toward small and focused problems.

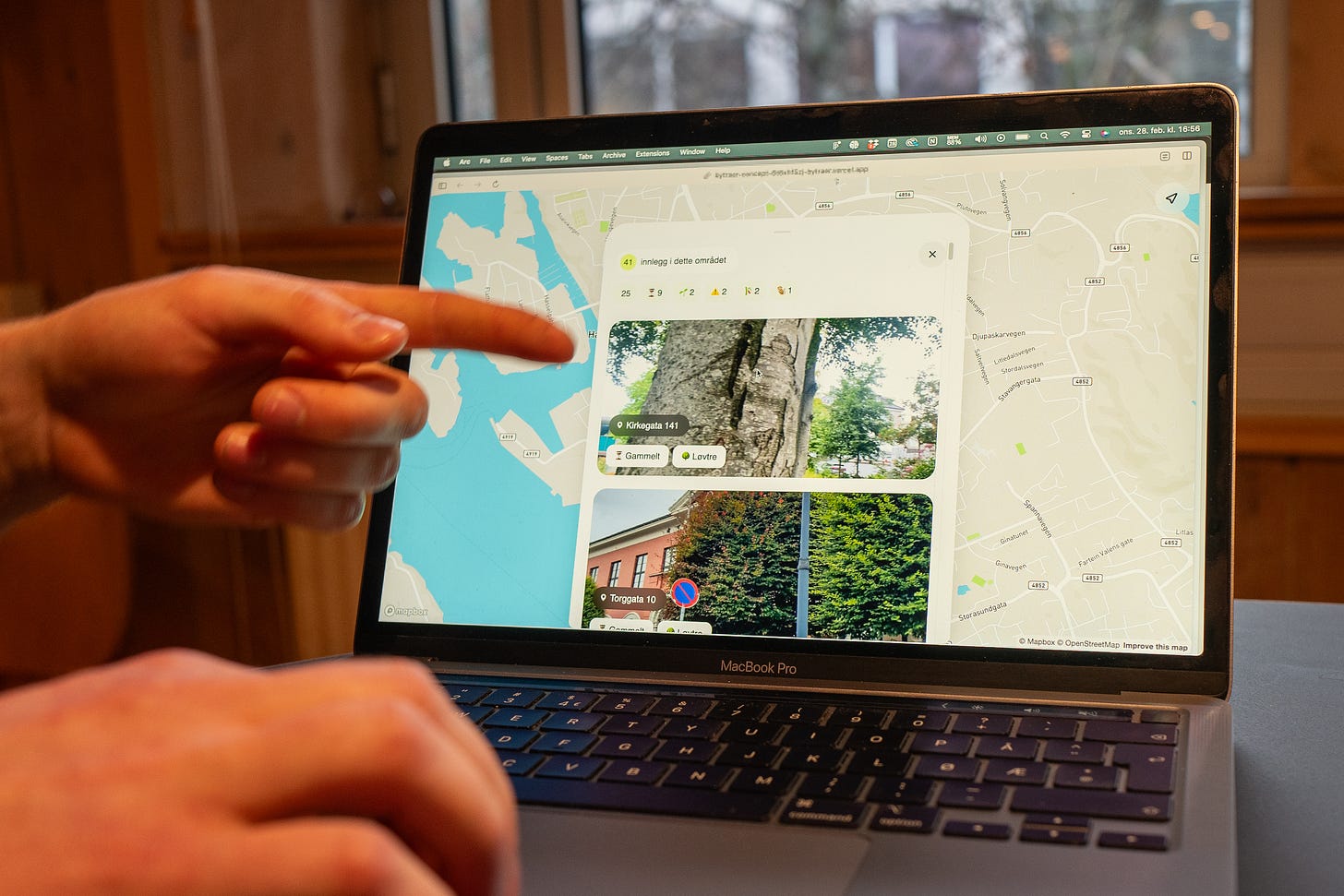

Erlend Grimeland and Elias Olderbakk of Travers demo’d a web app for school children to conduct a tree survey built for the towns of Haugesund and Karmøy (combined population roughly 100,000). Schoolchildren used the app while in the field with their teachers, so the app isn’t expected to do magic, but is instead part of a well designed service that connects children, teachers, and logical government in a collaborative web. Their data collection helped the municipality develop better data on biodiversity and carbon sequestration, as well as more qualitative aspects such as which trees are old, unusual, sickly, or good for climbing.

It’s an unnecessarily noble app for such a small user base, and that’s important: good citizen experiences, good data, and good management of public resources informed by data should not be a metropolitan privilege. Software can be cheap when you make it by hand; and handmade software can be beautiful.

Another example is a humble digital map that collects input from citizens about public spaces around town in conjunction with experimental furniture interventions. Did you like the bench? How do you want to use the space? What worked and what didn’t? There’s a powerful idea embedded here, which my tour guide for the day, Einar Sneve Martinussen, captured beautifully: cities should move at the speed of services, not the speed of buildings.

Waiting for new things to be designed and built in the “waterfall” process typical of the built environment is a formula for frustration. But reconfiguring existing spaces, maybe with bits of new furniture or other small scale interventions, doesn’t need to be so slow and it doesn’t need to remain in the purgatory of “placemaking,” which can be a synonym for temporary installation hastily made. Reimagining cities at the speed of services means designing desired urban experiences first and finding or building the material “props” and “sets” rather than starting with the physical intervention first and evolving a new way to act.

This is why interaction design and service design are more important to the future of cities than landscape architecture and architecture. It’s where new knowledge needs to be created. Humans have thousands of years of experience in building static and solid structures, and now a very robust recent history of building fluid digital services. Between the two there’s a possibility of a “slushy” urban space where solid physical interventions are planned and executed with the fluid techniques borrowed from digital design disciplines. User research, prototyping, iteration, and co-creation by citizens is what speed looks like in the built environment. Travers’ tools enable such speed, and the tools are beautiful pieces of interaction and service design in their own right.

There’s another aspect of speed that Travers is experimenting with, and that’s the speed of government. In my formulation, government moves at the speed of paper. Even with billions of dollars (trillions, maybe?) of investment in digitization the world around, most digital government services are the same as their pre-digital kin, just faster. Paying a parking ticket online or commenting on an urban development proposal via the web is not fundamentally different than doing the same in person, in city hall. That’s not a dig! Fast forwarding of tedious processes is helpful, but it’s also not the limit of digital technology in government. What about digitally native government services?

Travers have begun using large language models to summarize the plurality of inputs their micro apps receive. This shares the same spirit of g0v.tw in Taiwan using machine learning to facilitate public commentary at scale. The idea that, through technology, government officials can usefully receive more comments than can be practically digested and sorted by human staffers is an example of government at the speed of the internet. This is something to be both excited and cautious about. Developers experimenting in this realm need to weigh the emergent risks of future technology against the known flaws of status quo processes. Lucky for my urban technology students (and you too, if you’re excited about this kind of thing) the flaws of current processes for collecting input from the public about future plans for the built environment are many and significant.

On the topic of risk, it’s worth returning to a point above: the apps built by Travers are small on purpose. It means they can be built quickly and cheaply and that stumbles experienced along the way as well as technical debt are relatively cheap and “sandboxed,” or contained. This feels appropriate to the current historical moment when technology, government, and urban space seem a little fragile.

Democracy is a practice not a machine, so it lives in the decisions made each moment, with the best tools and information available at that time—it’s always a prototype. What visiting Oslo underscored is that small software can be part of the democratic practice. Software tenderly crafted and democracy steadfastly practiced don’t look all that different. Government at the speed of the internet does not have to mean giant software and monolithic databases; it can also mean small apps loosely joined.

🏋️ Need an intern for summer 2024? Reply to this email if you’re interested in urban technology students. They have skills in UX design, service design, python, javascript and a zeal for urban challenges.

These weeks: Kings of Convenience deep cuts on the train from Oslo to Copenhagen. A campus visit from Deb Chachra (more on this soon). Book talk event, studio visits, pin ups, and lots of welcomed feedback. Admissions and hiring. Designing and ordering new admit mailers and stickers. Snowbells are here. 🏃