Urban Technology at University of Michigan week -14

Last week we explored the semantics of the word “user.” This week we take a look at the old phrase “mind over matter” and ask it to show us receipts because when it comes to matter, there are always receipts.

Hello! I’m Bryan Boyer, Director of the Urban Technology degree at University of Michigan that will welcome its first students soon. If you’re new here, try this 90 second video introduction. While we launch the program, we’re using this venue to explore themes and ideas related to our studies. Thanks for reading. Have questions about any of this? Hit reply and let us know.

🧠🚧 Minds Change More Easily Than Matter

The most compelling public art in Helsinki, Finland is an accident that also offers a compact explanation of why it is so hard to apply the approaches of tech to the built environment. If that sounds unlikely, hang in there.

Helsinki’s a city with no shortage of beautiful moments in the public realm. If you want the most poetic public sculpture, visit the Sibelius Monument, designed to be an expression of the famous composer’s music. If you want the quirkiest, visit Peeing Bad Boy, and make sure you keep your distance. For the first four years I lived in Helsinki the globe-holding sentinels who guard the entrance to the train station were my favorite. (Side note: the station was designed by Eliel Saarinen who taught architecture at UM in the 1920s. More proof that Michigan is the Kevin Bacon of US states.) But then an old logistics railroad cutting through the middle of the city was renovated into a recreational trail for cycling, walking, and skating (similar to Detroit’s Dequindre Cut). It’s this last bit that led to the current reigning champion of best public art in Helsinki. 👇

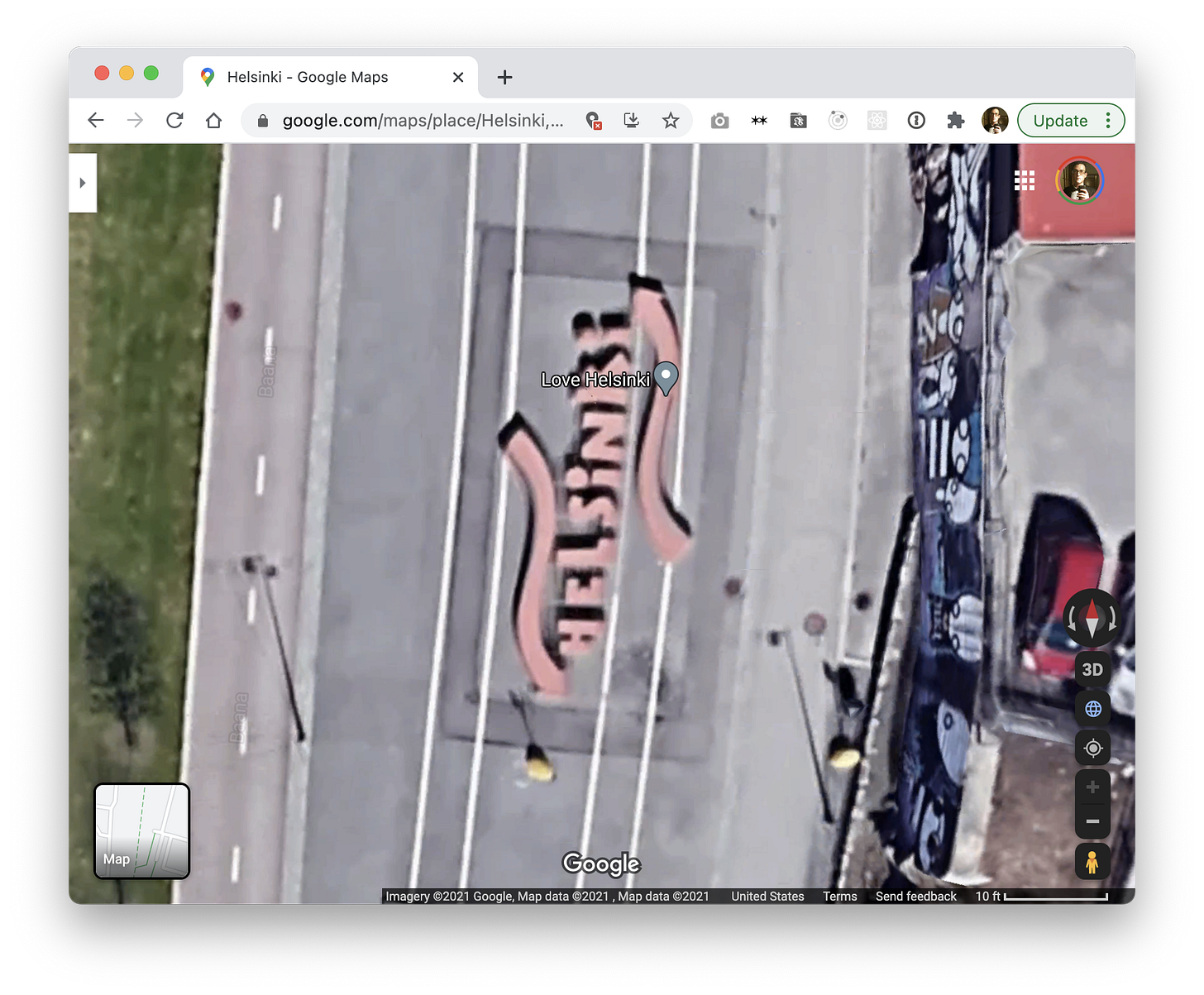

What you see above are extruded letters that say “Helsinki” with squiggly arrows to the left and right. It’s a sculpture/bench designed by skater-turned landscape architect Jaane Saario, which was a great choice because this was intended as a mini skate park. He was hired by the City of Helsinki to create something for skaters and the result was this set of extruded letters and shapes perfect for skaters to grind. But that’s not the public art I’m talking about. The rectangular stripe of gravel around the words Helsinki is the art, and it was completely unintentional. See the apartment buildings in the background? When the “Helsinki” skate sculpture was unveiled skaters did what what they do and some nearby residents complained about the noise.

In a show of government responsiveness, the Deputy Mayor who was responsible for the Public Works department heard those complaints and announced a solution in no time: the skating would be stoped by making it impossible to get a running start. The killjoy solution was to trench a channel around the sculpture and fill it with tasteful but un-skatable gravel. You might be asking why they didn’t try putting up a sign with hours of use, and that would be a good question. From the perspective of the complaining neighbors, it’s pretty magical that a Deputy Mayor would hear them directly and react to “fix” the issue within days. +1 for responsive government, right?

But if you’re a Helsinki skater—a taxpayer just like the well-heard neighbors—that quick response from the Deputy Mayor looks instead like an autocratic decision made contrary to and outside of the public process that was followed to approve, design, and commission the whole Baana recreational trail and its tiny skate sculpture. If public process is followed to build something, shouldn’t public process be followed to demolish it, the skaters asked?

And they were right. Within weeks, the Deputy Mayor reversed course and this scar around the skate sculpture was filled back in with new asphalt tarmac. Today the whole thing lives on as an enduring commemoration of the challenges that come when you literally set decisions into stone. Minds change more easily than matter.

If we return to the table from last week, the story of this skate sculpture gives us a tool to think about the Risk Mitigation and Legal Perspective rows below. Building the skate sculpture followed a planning process (slow but deliberate and legitimated by the state), but responding to the neighbors embodied the spirit of prototyping (fast and often in a legal or procedural gray area) which was then redoubled when the asphalt was filled in again. Whereas the original construction followed an “ask for permission” process, the demolition was done hastily under the authority of the Deputy Mayor in a mode of “ask for forgiveness,” and in fact that forgiveness was not given, which is why my favorite public sculpture exists today. The scar had to be filled in.

Responsiveness in government cuts both ways. Which do you think was greater?

The anger of the neighbors who didn’t like the skate sculpture initially

The joy they felt when the skate sculpture was torn up

The anger the skaters felt when the skate sculpture was torn up

The joy of the skaters when it was repaired

The anger of the neighbors when it was repaired

The consternation of the Deputy Mayor trying to keep everyone happy

Just like expanding a highway induces more demand for vehicular travel, this example implies that when government becomes more responsive, communities become more demanding (that’s good). When new groups of unhappy constituencies are minted thanks to hasty changes, they demand quick action in return. If things are shown to be able to adapt quickly and easily, communities expect them to—as they should. Finland is a place of relatively even-keeled politics, but what would this volatility of the built environment mean in a country with the politics of the US? As we explored in the wake of r/wallstreetbets wreaking havoc on Wall Street, digital NIMBYism or algo-NIMBYism is likely to be more disruptive than the static version we live with today. Solve this and you’re a genius.

In the case of my favorite public art in Helsinki, the "responsive decision making” resulted in a flip flop with three sets of material consequences—the build, the scar, the repair of that scar each involved a construction crew. If you’re still thinking about who of the groups listed above have the strongest opinions about the outcomes of this situation, consider another option entirely: the taxpayers who paid for the construction and demolition and repair of the sculpture. All because a planning process turned into a prototyping process by accident.

Do not read this as a critique of prototyping, however. On the contrary, it points to an opportunity to think more carefully about how and when decisions are prototyped in the built environment and the role of technology to ease this work. What’s problematic in the Helsinki story is the abrupt transition from planning to prototyping. If a community such as the residents of Helsinki expect an incremental and risk-averse process (traditional planning) arriving at stable and enduring results (the Baana trail), it would be (and was) jarring to then have that process (and the skate sculpture) accelerated in response to a tiny minority of the stakeholders.

Prototyping is an approach that harnesses what we might call “productive volatility” to enable a group of people (citizens of the City of Helsinki) to explore a range of options and tinker with them until the results are widely agreed to be optimal. That’s all well and good when it’s done in workshops with post-it notes, or completed with cheap and light tools like Swiss “ghost buildings” that show up before the real thing, or via digital tools, such as Berlin’s crowdsourced Smart City strategy, but it comes with a different order of magnitude of costs attached when each prototype is built. Plus you have to look at the scars forever.

When geofencing allows streets to be closed to vehicular traffic rapidly and without the cost associated with bringing out traffic cops or erecting signage, who and how will community decisions be coordinated so that individual “good” decisions do not lead to collective bad results? Sounds like a great place for smart contracts, but is that fair if some don’t know how to read such code? When power is produced locally and shared between neighbors on a totally non-Zombie microgrid, what happens when Sam down the block pisses everyone off? When the brightness of a street light is responsive, will we argue about the lighting level or also about how often we, as a community, are willing to argue about changing the lighting level?

BTW - if you’re interested in how crowdsourcing and crowdfunding meet the built environment, I wrote a book on the subject when I lived in Helsinki. It’s called Brickstarter and you can download it for free, thanks to the Finnish Innovation Fund SITRA.

Links

🤗 London’s community crowdfunding initiative released a big report this week. The intro is written by Dan Hill (co-author of Brickstarter) because it’s a small world of folks who are blind to the distinction between physical and digital, so help us make it bigger, ok?

🎨 We’re excited about the Feral File Social Codes exhibit opening tomorrow.

🎮 On the topic of pure beauty, Matthew Lyons’ 3D imagery built in Unity is sublime. The Environments loops are a nice thing to stare at for a while on a Friday.

📺 If you want to combine thing of beauty with “antiquated technology” check out this short clip about the man who maintains a 40yr old machine, one of only 10 ever made, that animates text and simple imagery without a computer.

🤖 Also excited for our colleagues at Michigan Robotics who have a shiny new building and a legit Mars Rover. Hey Michigan Robotics, can we play with your toys?

This week: Reviewing resumes. Talking about studios. Lining up meetings. Joined Malcolm’s review. This week was all parts no wholes. 🏃♂️