This year in the inaugural Cities Intensive we’ve been to Toledo to learn about water, Chicago to learn about mobility, Detroit to learn its histories, and now Grand Rapids to learn about land use. This newsletter marks the end of our field trips for the semester, and just over a week before the very first year of this program comes to a close.

Why trips? Because the best way to understand city making is to see how lots of them have been made. Boarding our trusty bus once again, we made our way from Ann Arbor to downtown Grand Rapids with multiple stops along the way to do exactly that. Zooooom!

💬 Hello! This is the newsletter of the Urban Technology program at University of Michigan, in which we explore the ways that technology can be harnessed to nurture and improve urban life. If you’re new here, try this 90 second video introduction to our degree program.

🌱🏙 From the Soil Up

“Modern society is built on $&@%,” noted Dan Wells while we stood in a field watching a tractor full of manure amble by, "and there it is." Civilization starts with agriculture, as Dan described. Cities literally start with soil. Houses and stores and factories and all the other myriad land uses that are critical to the daily function of a city consume open land to produce urban space. At its core, the decisions a community makes in response to this simple tradeoff are what define the characteristics of the place that eventually emerges. A city's relationship to land is primary.

Twenty-four hours later and 10 miles away, we stood in Grand Rapids’ Martin Luther King Jr. Park learning from Alita Kelly, who shared her work as an urban farmer, advocate, proprietor of South East Market, and creator of Freedom School. That last item is about “reclaiming our space (in nature),” as Alita noted that Black and Brown kids do not have much open green space in southeastern Grand Rapids. “[We're] trying to give kids in the neighborhood agency over their community” by spending time in nature, and getting them involved in planting and agriculture. If cities start with soil, communities are sustained by it.

Freedom School emerged from South East Market, which Alita created with her partner Khara Dewit to protect "food sovereignty" and push against "food apartheid," terms being used very intentionally in contrast to the description of "food deserts" that often gets used in well-meaning planning circles. In Alita's words, the name food apartheid points to the systems at play that prevent food from being accessible. Those systems include land use, zoning, and finance, which were all under the microscope for our group on this trip.

Not far from South East Market, a larger development project is underway that is poised to shift the vibe of the neighborhood. Cities change, but how that change happens is the critical question. Standing in Alita's grocery store we had a frank, balanced, and wide-ranging discussion about gentrification, community engagement, and local capital. “[The developers of the large project] didn’t ask how [we in the neighborhood] want the development to be. They asked, ‘alright people, what color do you want the building to be? What name do you want for the brewery?’” explained Alita's partner Sergio Cira-Reyes. “But people here don’t exactly drink a lot of craft beer.”

These two visits capture the purpose of our trip this week: what are the fundamental tradeoffs of urban development and city making, and who has a say in how those tradeoffs are made? Data, computation, and networking are implicated in both of these because it's 2022, but technology doesn't matter in the slightest if the fundamentals are wrong.

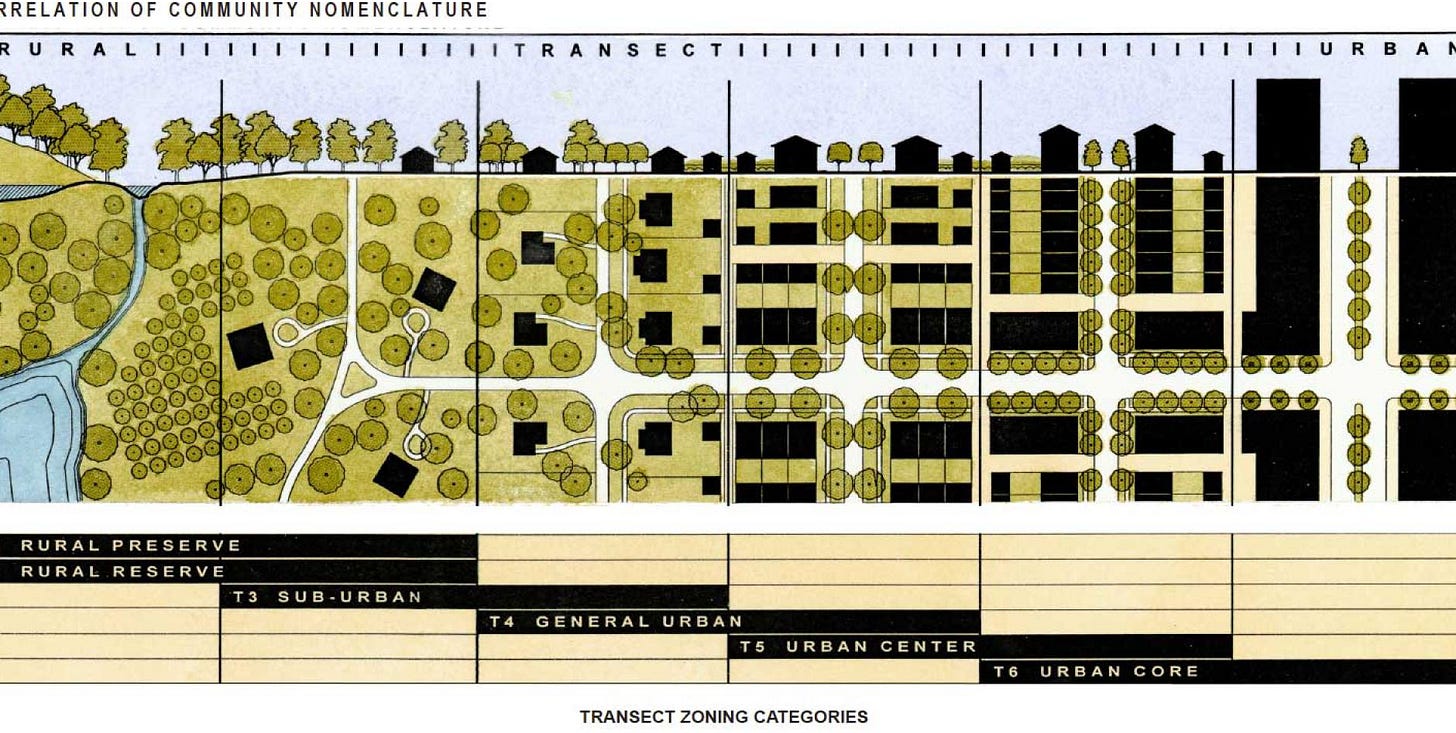

The trip was dedicated to understanding land use by making stops along the transect and meeting with folks as we went. With Dan and his colleague Natalie Davenport we toured the more rural end of the transect in Gaines. “Transect” is an urban planner argot that describes the spectrum from untouched wilderness to city center. It comes with a handy diagram that is helpful when you need to be more precise about place.

As our bus traveled through space we were also traveling through time. With each huddle we dropped into a different type of urban settlement, popular at a different moment in American history. From the manure-sodden faming plat that looked identical to how it would have in the 19th century, to an early 20th-century arterial road with small-scale commercial development, to walkable residential neighborhoods with dense detached housing from the 1950s: the start of our tour was a glimpse of what cities were like before vehicles and parking became preoccupations of American life.

A few blocks and a decade or two away we were in postwar urbanism. The houses are maybe 10% bigger, but the lot sizes have grown also, and sidewalks have melted into the manicured lawns of the neighborhood. Streets dead-end in cul-de-sacs. Two-car garages show up adjacent to the front door of homes rather than tucked around back. The neighborhood, because we visited in the middle of the day, was dead. Privacy and independence was nearly terminal from a civic perspective. Manicured lawns though.

Gaines Township has recently denied permission to a mixed use development that would put 500 homes, commercial, and retail on an 80-acre site that would otherwise be—at best—82 homes. “It’s not necessarily a fight, but I need to educate people that dense housing can be” a great part of the community, Dan explained. He and the Township are wrestling with the math problem that is inherent to Euclidean zoning. When cities are planned using Euclidian principles (in a nutshell: houses here, shopping there, factories over yonder) density is low and there are “parking lots e-v-e-r-y-where.” Dan's syllables stretched to the horizon.

On the theme of time travel and how spatial decisions change (or don't) over generations, Euclidian zoning also creates strong path dependency. When things are spread out, it gets costly to have utilities, so homes on the fringes have septic systems. That shifts the cost from a shared tax base to an individual home owner, and marginal costs inch the line of housing attainment just a little higher, leaving just a few more people excluded from access to affordable housing options.

Same goes for mobility. Stretch a city out and the overlaps between people traveling on any given route segment tend to decline. Public transit can be designed to work in low-density areas, of course, but it never really thrives in hinterlands and suburbs. Transit works best when the necessities of life are clustered together. To get from one part of Gaines to the new Amazon fulfillment warehouse just a couple miles away it would take a two hour bus ride. Why? Because the route would take riders into Grand Rapids and back out!

America is a quilt of jurisdictions from the local to the federal, and collaborations horizontally across peer networks of cities. This produced a rich thread of discussion during our time in and around Grand Rapids about economies of scale. Smaller municipalities share some things but others. Interdependence is accepted for the sake of lower cost when absolutely necessary, but independence is still prized. The Township of Gaines (pop. 426), for instance, shares water and sewer with Byron, MI (pop. 586) but does not collaborate on a unified urban planning vision. We share our toys in America, but not all of them, and not all the time.

America's wealth in the postwar period is the enemy of today's urbanists. Prior generations of planners and decision-makers committed the country to a largely suburban life, and the resulting investments have manufactured not only homes and strip malls, but path dependency. To change the settlement patterns of the country now, with the accumulated weight of past decisions literally cast into concrete highway interchanges, utility trenches, and parking pads, is no easy feat.

It may not be easy, but it is possible, as we learned from a visit to Wyoming, MI's city hall where we were hosted by Jordan Meagher, urban planner; Myron Erickson, Director of Public Works and Utilities; and Curtis L. Holt, City Manager. Wyoming is 15 minutes from downtown Grand Rapids and looking to grow via planned unit developments (small mixed used districts), rezoning to allow for higher density, and the allowance of additional dwelling units. I'll be honest: before Jordan and his colleagues shared the city's plans, I did not expect to hear such careful thinking on ways to increase density from a community of this size.

But then again, Wyoming, MI seems like a pragmatic place that does not let a good idea go to waste. In a wide-ranging discussion about planning, public works, municipal government, and public utilities, we came to the topic of salting roads in the winter. In the past the city used 800 lbs of salt for every lane mile of roads, with air temperatures as the deciding factor for when to salt. But cold air doesn’t produce driving hazards, it's cold roads that do that! Road temperatures are a better way to assess the need for salt, and with the adoption of small, light pole-mounted sensors, the town was able to reduce its salt usage by almost 60%.

That's 60% less salt paid for and wasted, less carbon expended on the trucks to distribute it, less salt melting into water supply, and—yes—even 60% less salt glomming onto car bodies and rusting out private asset value.

As Myron described, the city didn't have computers when he started working there nearly 30 years ago—“we didn’t have the internet, we didn’t have email"—and now, as his colleague Curtis noted, "the city cannot operate without computers.” That sounds like progress, and in large part it is, but path dependency rears its head here in a different way. When the city becomes dependent upon data, computation, and networking to operate, it also exposes new vulnerabilities, so Curtis and his staff have added cybersecurity to the long list of municipal operations needs.

At Downtown Grand Rapids Inc. we zoomed into questions of municipal vitality. Thanks to Mark Miller and Marion Bonneaux, that discussion was surprisingly free of acronyms for a group whose work is an amalgam of downtown development authority (DDA) + business improvement district (BID) + tax increment financing authority (TIF). The focus in Grand Rapids’ downtown core is really to make greater use of the assets already in hand. So much of the city’s core is working well already, but how can it be better, and for more people?

The river, for instance, is a defining feature of downtown, yet swimming in it is illegal. Like most American cities with waterways running through them, this decision made good sense during industrialization. Today, when use of the word "log" is more likely to refer to text files on a server than a felled tree floating down the Grand River, it seems as though the question of "how to live with the river" demands new answers.

Data has a role to play in finding these new answers. As Marion noted in our discussion, using technology to gather better insights and understanding from the community about their needs and desires is one example. So is using quantitative analysis to find opportunities that may not be obvious, such as triangulating the complex set of considerations that factor into an office or retail brand choosing Grand Rapids as their next location. Such distanced analysis of place through data can produce suggestions that don't match with lived reality, though. Would Grand Rapids be a prime location for the next IKEA, one of Marion's algorithms asked her? Unlikely here in the home of American furniture giants Herman Miller and Steelcase! "Sometimes it's better to be data-inspired than data-driven," Marion concluded.

Our colleague Toban Shadlyn speculated about the systemic changes that would need to be undertaken to make the river accessible again. Or for that matter, to align the land use of the city with human activity and desire more intentionally. In Grand Rapids (and most American cities) the majority of the public-owned land is not in use as parks or some supporting use like water treatment, but as roads. 25% of Grand Rapids is road. How mad would you be if 25% of your home were hallway?

Cities have nibbled at reclaiming space for people through initiatives like Parking Day and Open Streets, and those efforts found an unexpected ally in the form of COVID adaptation, but such small examples of trading space for cars into space for people are not going to add up to a transformational shift of American settlement patterns.

Land use is not merely a story of swapping fields into homes or homes into offices, but of dreaming together in very slow motion about how we want to be a society. Changing the city means changing who is involved in the decision-making, what options are considered as legitimate alternatives to the status quo, and what sources of evidence are accepted as meaningful to public debate. From what soil do your dreams emerge? Do you dream in tidy crop rows or dense thickets? Do your dreams leave room for undergrowth and overgrowth? Are you confident enough to dream together with neighbors and peers who spring from different soil?

And with that, our tired students boarded the bus for one final trip back to Ann Arbor and the conclusion of the Cities Intensive in ten days time. Dreaming together, indeed.

🖼 Postcards from Detroit

Our Detroit trip fell on an off week last week, so just a few snapshots will have to do! Marsha Music spoke with us about Black Bottom and Lafayette Park; Ford toured us around Michigan Central; and Raquel Garcia of SDEV and Darren Riley of JustAir gave us a download on environmental justice in Mexicantown.

These weeks: On the road. Drawing. Procurement. Lining up a summer research assistant—welcome, Janielle! Preparing for the punk rock Sim City finale of the semester. 🏃