Urban Technology at University of Michigan week 100

Ending the Cities Intensive by building an Incomplete City

Seven weeks ago we started the very first Cities Intensive. Since then we’ve traveled to Toledo, Chicago, Detroit, and Grand Rapids while reading about, looking at, exploring, dissecting, drawing, and generally devouring urban environments. And to wrap it all up? Punk rock SimCity!

💬 Hello! This is the newsletter of the Urban Technology program at University of Michigan, in which we explore the ways that technology can be harnessed to nurture and improve urban life. If you’re new here, try this 90 second video introduction to our degree program.

🎸 Punk Rock SimCity

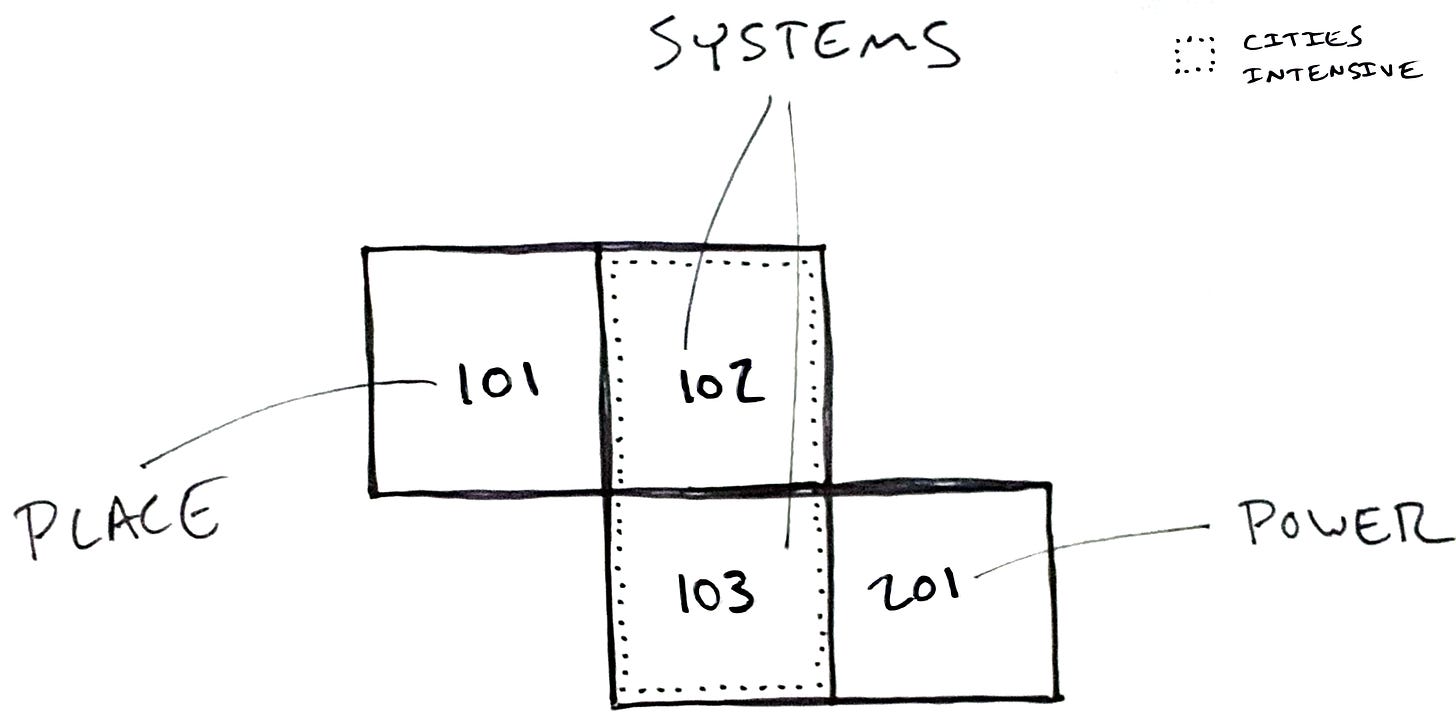

This semester plays an important role in the overall sequence of required courses for Urban Technology students. The goal is to give students tools to understand urban environments they’ve never been to before, which is accomplished by pairing two courses that take different-but-related perspectives on urban systems. UT 102 looks at the “Anatomy of the City” through the lens of three core systems (this year: water, mobility, land use), whereas UT 103 is a design workshop that introduces students to design methodologies and provides a venue to apply what they are learning in UT 102. Together these courses, led by Phil D’Anieri and Toban Shadlyn respectively, form the Cities Intensive. This is what it looks like as one of the Tetris blocks that make up our curriculum:

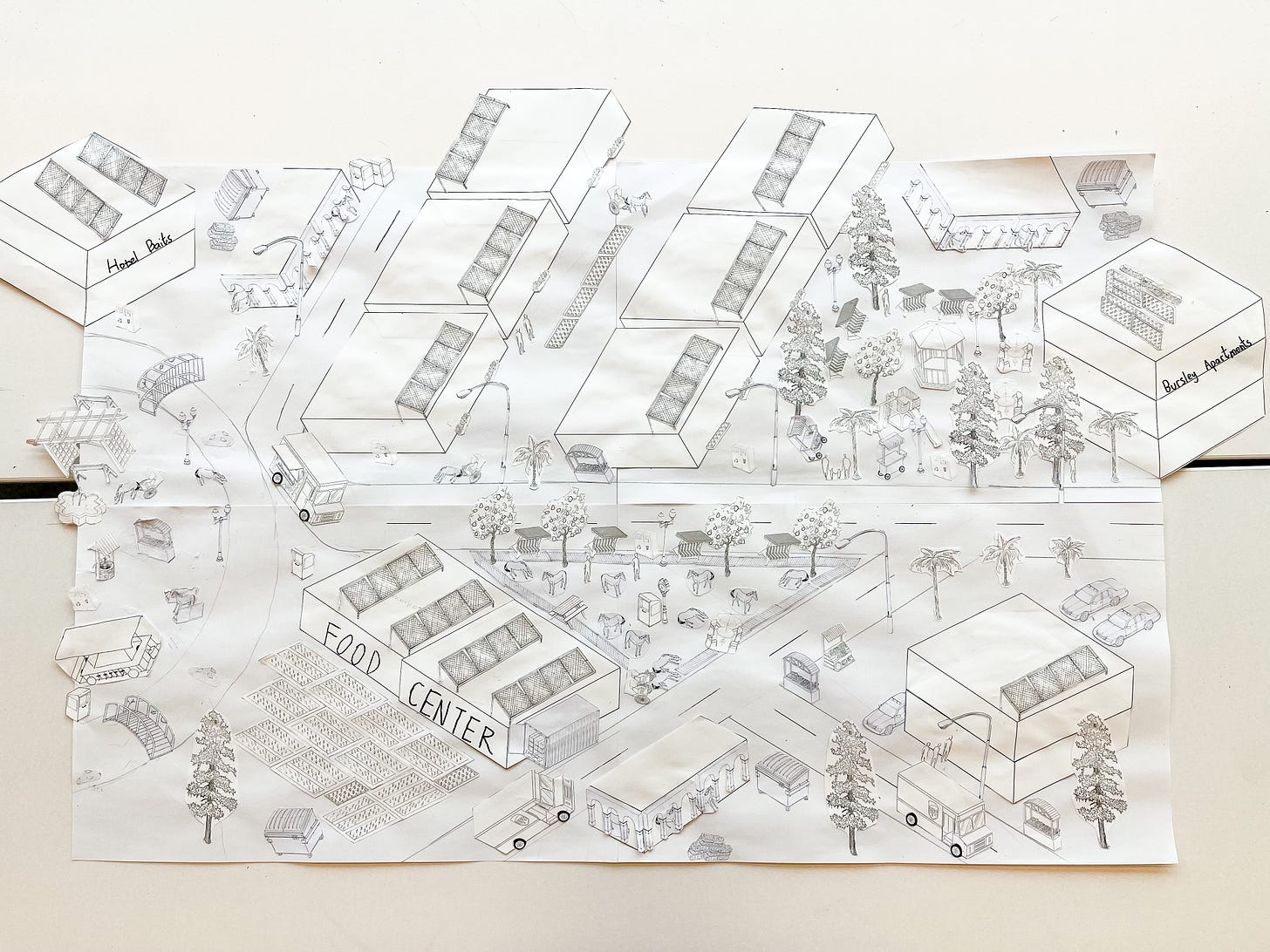

The final assignment in UT 103 is a workshop/game called The Incomplete City, where students have an opportunity to apply the learnings from both classes to one cumulative, hands-on project. This happens by creating a mural of a city seen in isometric view, drawing everything “smaller than a building, bigger than a cell phone,” as Dan Hill put it. And he should know, because he was one of the original creators of the IC concept, together with Joseph Grima and Marco Ferrari. They ran the first IC workshop back in 2016, we brought it to U-M in 2019, and based on the response to that beta test we’ve now integrated Incomplete City as a regular part of the urban technology curriculum.

The term “punk rock SimCity” is an attempt to capture the vibes of the workshop. The idea is to draw and collage an isometric view of a place, then grow the imagined population of that place until it’s a city. Our students began by brainstorming a list of specific—and slightly quirky—user groups with distinct needs and spatial considerations. Here are just a few: retired Olympians who still like to compete, equestrians with a 100-mile diet, fisher-people who live away from their families (and love bowling), people who are camping enthusiasts and savvy social media users. Creating these extreme and unlikely “residents” provides a useful constraint for students to grapple with and begin designing the first 7 neighborhoods, each housing a population of ~100 people.

Each neighborhood is assembled from “wallpaper” sheets of urban elements ready to be cut out, copied, pasted, or embellished with a pen. Working on paper is great because elements can be multiplied up or down in scale with a photo copier. It’s a tactile process, like using the skills of zine-making at the scale of a wall.

Eventually the seven neighborhoods were merged into pairs, setting off rounds of negotiation to find the overlaps in needs, assets, and lifestyles between the various user groups. Drawing becomes re-drawing. Cut and paste becomes careful lifting off and repositioning. Drawings change; neighborhoods evolve.

As the city continues to grow and merge, the negotiations become more nuanced. Toban dropped some surprises on the group as things went: more people are looking to move in, so add more housing! What about the natural environment? How do people get around?

As incomplete villages merged into one Incomplete City, decision-making came to the fore. The group self-organized into a quasi government, complete with departments for needs like construction, mobility, and “problem solvers” who functioned as something between a mayor’s office and an advisory council.

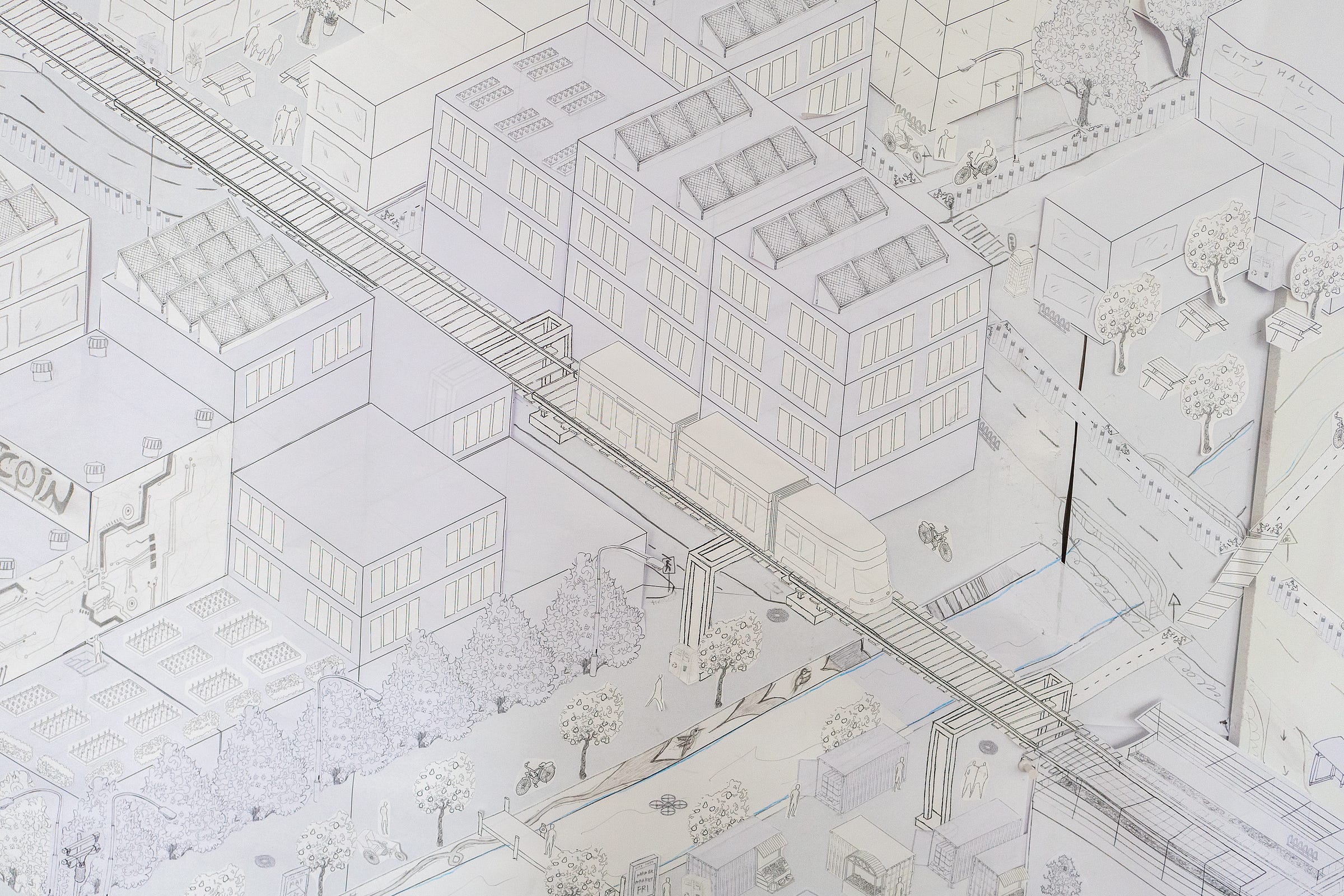

After a burst of work on the mural over a number of days, students rushed to put finishing touches on the wall Monday morning in anticipation of hosting guests for a wrap-up discussion. We are grateful to have been joined by Hannah Mae Merten from Bedrock Detroit; Michael Mogenson from Ford Next; Komal Doshi of Ann Arbor SPARK; Ben Garcia, a 5th-year student in Architecture; Ann Burke from U-M’s Center for Socially Engaged Design; and Taubman colleagues Rob Goodspeed and Phil D’Anieri.

The city—named Tobanville in homage to the professor who led the course—features seven markets in seven different parts of the city, one for each day of the week. Roofs above four stories are expected to have solar and those under four stories should have urban agriculture. Citizens of Tobanville enjoy a lake/sea on the western edge, providing an income stream for fisher-people, and mountains to the east, which are favored by camping and snow sport enthusiasts.

Take a look at the final mural. Walking into a room with a 20ft x 6ft drawing on the wall is a visceral experience. It’s so huge and detailed that the effort of creation is evident even if you do not engage in the details of the urban design on display. And yet, with so many acts of decision-making literally on display, what’s amazing is how many assumptions still linger around the Incomplete City.

Our guests zoomed into these assumptions almost immediately. During the final discussion they asked: what climate does the city occupy? At what point in time is the city situated—now? What’s the income level of the people who live here, and is it all the same? Is there any informality in this city? No doubt these questions were voiced and discussed by our conscientious students during their many hours working on the mural, but perhaps not conclusively. This, too, is a learning point: in cities the only thing more scarce than space is neutrality. What you do not make decisions about still happens. Abstaining to plan is not the same as prevention. If you’re not careful, assumptions become policy.

The city that emerged, as incomplete as it stands, is nothing if not optimistic. Hannah Mae challenged the students to “take the values of this [city with very few vehicles] and apply it to a world that has already been built for cars.” Phil noted that the town features solar panels and biogas facilities, but that the scale of them may be off. In plain terms: are there really enough solar panels to power the city? And what about battery storage for low-generation days? One of the things we will need to work on for future years is an additional set of guidelines to help participants steer well clear of “cosmetic sustainability,” as Phil phrased it.

Useful meta-observations about the process of the workshop itself also emerged in our final discussion. Rob noted his discomfort with the “critic” role that is so common in architecture circles but less common in planning, and a role that Toban and I had inadvertently invited guests into. As Rob explained, “in the real world of planning everyone has an interest,” which I take to mean that the Incomplete City workshop will grow in richness the more we can bring the complex, competing, shifting dynamics of personal interests and biases into the classroom.

On that note, there’s also the question of people. No polite, human-centered design process begins with making up imagined users, and yet that’s exactly what we did. “Throughout the activity, the students wrestled with the tendency to design for an abstract idea of ‘humans’—everyone and therefore no one—versus grounding their decision-making in designing for ‘extreme’ users with unique needs,” Toban explains, but these extreme users were still only imagined. It was uncomfortable to work from assumptions, and that’s OK... for now. Part of what comes later in the curriculum is a backfilling of research abilities so that students have a wider set of tools to understand humans, their behaviors, and this lively thing we share called society.

Wouldn’t it be interesting if we asked these students to do Incomplete City again in their final year at U-M and they insisted on developing user groups from actual, situated research? How that would change the game! The seemingly simple question of constructing user groups or personas from actual research for a project like Incomplete City is fiendishly complex because it becomes a question of representation, and therefore of power. It’s also a question of scale and resources: namely, how can one get to know a complex system like a city in a bounded amount of time? We think it’s about finding the right balance between design research and quantitative analysis. This is one of the many things that we’ll be working on in forthcoming semesters because it is critical to breaking out of the caricature gaps between the practices of urbanists and technologists.

No classroom exercise can be a real simulation of urban decision-making; cities are too messy to abide that kind of simplification. Rather, the Incomplete City is a way to internalize the interconnectedness of urban systems by imagining them and the society they serve. It’s an exercise in drawing out the reciprocal relationships between systems, place, and people. And it’s a heck of a lot of fun.

☀️ Have a great summer and see you this fall. We’re taking a hiatus until then.

These weeks: Video production! Facilities! Ending the semester. Cleaning up the studio. Ramping down and trying to take a beat before we ramp back up. Wowowow - 100 weeks of this already behind us. 🏃