Urban Technology at University of Michigan week 148

Normcore Urban Technology in Cleveland

We’re just back from Cleveland where the first year Urban Technology students were studying land use on their third and final field trip this summer. In about two weeks the Cities Intensive will conclude, students will depart, and we here at Taubman College will spend the rest of the summer in reflection and iteration mode. But first, some notes on the low key urban technologies we heard about in Cleveland and what they imply for the future of cities.

💬 Hello! This is the newsletter of the Urban Technology program at University of Michigan, in which we explore the ways that data, connectivity, computation, and automation can be harnessed to nurture and improve human life in cities. If you’re new here, try this short video of current students describing urban technology in their own words.

⚙️ We’re hiring a Program Assistant to help with the day to day operations and growth of the Urban Technology degree. Interested?

🌳 Can Normcore Urban Technology change how People See, Shape, and Spend Time in Cleveland?

Like last year’s trip to Grand Rapids, this year’s adventure in Cleveland was organized as a tour of the “transect,” which is a helpful diagram that describes varying levels of urban density from the rural hinterlands to the urban core. We got to Tower City, the in the middle of downtown, via stops in Elyria, Avon, Rocky River, Lakewood, and the Tremont neighborhood of Cleveland. The transect is not some kind of universal truth, it’s just a useful simplifier that helps us think across geographies in parallel with taking a close look at the situated reality of a specific place.

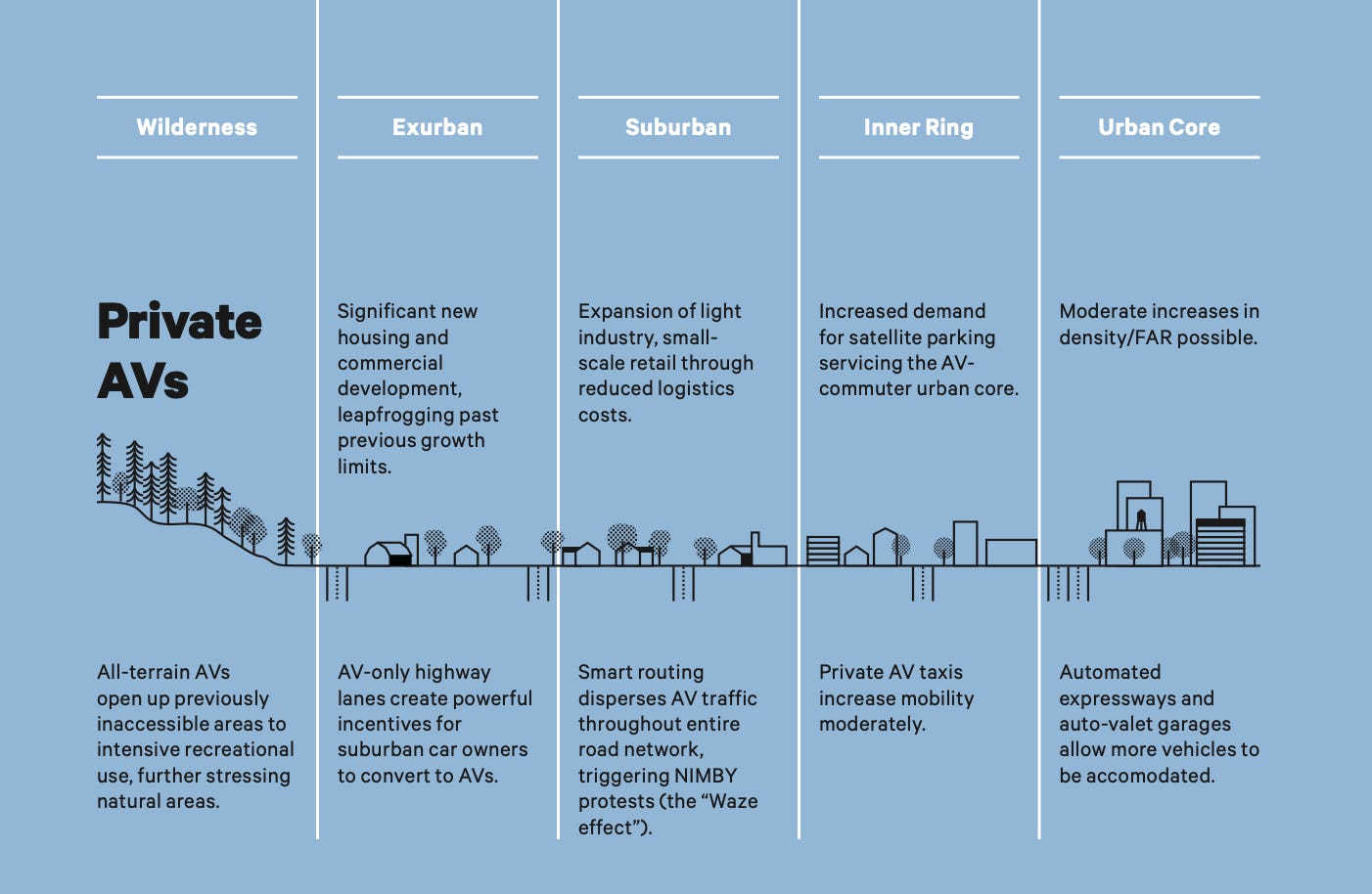

Let’s borrow an example of the transect from a prior project that I did with Bits & Atoms (Anthony Townsend) for Bloomberg Philanthropies and Aspen Institute’s Initiative on Cites and Autonomous Vehicles. The diagram below describes potential behavioral and urban planning impacts spurred in a scenario where autonomous vehicles (AVs) are predominantly privately owned (versus being owned in a fleet by Lyft, for instance). This assumed a pretty generic idea of North American cities from the pre-COVID era where the downtown is bustling, even if small. The thinking that went into the diagram below assumed downtowns would continue to be the jewel of metropolitan areas.

When the Urban Technology bus stopped for a visit at City Hall in Lakewood, an inner ring suburb, I was surprised to learn that it’s the densest city in Ohio with nearly twice as many people per square mile as Cleveland. Meanwhile, downtown is filled with voluminous and desolate parking garages. Combining these two observations tells me that a private AV scenario might play out differently in post-COVID Cleveland, where downtown has plenty of parking and only modest office demand. A plausible result could be an inversion of the urban core and inner ring descriptions in the diagram above, leaving the core to densify with infrastructure while outlying neighborhoods and nearby towns form a green ring, flush with commercial activity and the lush tree canopy that gives Cleveland it’s nickname of “forest city.”

Not if Bedrock has anything to say about it! They are the real estate development firm that owns the hulking Tower City complex facing the Cuyahoga River right in the middle of downtown Cleveland. Our last stop was to hear from Kate Gasparro, Head of Land Development, about their proposed redevelopment of Tower City to add millions of square feet of mixed use housing, retail, office, transportation, and public space while connecting the “core to shore” with a project beautifully designed by David Adjaye. The project proposes to make downtown the unabashed center of the city, both literally and conceptually. It’s going to take 15-20 years to build, so those AV scenarios above are likely to not be so theoretical for Tower City.

When we started the Urban Technology degree program someone rightfully asked, “what is urban technology?” At the time the most common definition was to cite sectors or verticals using the industry habit of making -tech portmanteaus: infrastructuretech, govtech (government), proptech (property), contech (construction), and so forth. While descriptive, it’s also a reflection of trends and market activity more than it is a definition. In our words, urban technology is the use of data, computation, and connectivity to change how people see, shape, and spend time in cities.

The point of these trips is to learn about cities by diving into their complexities through meetings and tours with leaders from a mix of different sectors. Students are learning about the ‘anatomy of the city’ first and foremost. “The” does a lot of work in that sentence because this course is about learning how American cities work as a typology, not how “a” city works. Detroit, Chicago, and Cleveland are lenses through which to learn. We could have just as easily focused on land use in Chicago or Detroit.

Of this trio Cleveland was the most normcore. It’s not a particular hotbed of urban tech like New York or Detroit, and it’s not a super-heated urban development market like Austin or Atlanta. That’s not a dig at all, it’s an asset. Cleveland’s normality is useful because it reveals the extent to which urban technology is integrated to the practices of city planners, developers, and other working in the city. Here are some of the examples that came up organically during two days of conversations around town:

See: air and water quality sensors, online platforms for community engagement…

Shape: fiber optics, mass timber construction, parametric design, augmented reality visualizations, AI as ‘translator’ between construction trades and developers, microgrids…

Spend Time: internet connected access control, surveillance/security devices, payment systems, ebikes…

For every big-hype example like autonomous vehicles there are 100 small ways in which the built environment is being connected, automated, and reinvented. The cumulative effect of these “small pieces loosely joined” is important precisely because of its humility. Cities are not products and they cannot be bought or sold as singular units. Diffuse and disconnected small scale innovations being applied by a variety of actors is what builds the potential for new urban collaborations. Technical innovations get bought, but cultures of innovation have to be built—and it takes some time.

The built environment has long been one of the sectors most “resistant” to digital technologies and automation. Change in cities is often slow, and change in city-making even slower, but the trip to Cleveland showed signs of urban technology becoming normalized from city hall to the construction site.

We should pay attention to the prestigious real estate developer using parametric modeling or the local citizen scientist deploying an air quality monitor, but we should be really interested in what happens culturally, socially, and economically after both of those examples (and the others above) become normal.

These weeks: Facilities. Recruiting. Preparing to go to Copenhagen with a group of planning and architecture students. Adding things to the ‘list of stuff to do over summer’ that is already too long. Cyber whistle. 🏃