Urban Technology at University of Michigan week -02

Jonathan Massey on why today's platform urbanism is not good enough (yet)

In this week’s newsletter, Taubman College Dean Jonathan Massey continues the thread on platform urbanism from last week by introducing the question of tradeoffs. When you get the benefit of convenience from a ride-hail app, what have you given up? More importantly, who sets the terms of those tradeoffs, because they are far from static.

Hello! This is the newsletter of the Urban Technology degree at University of Michigan, written by faculty director Bryan Boyer, to explore the many issues and themes at the intersection of cities and technology. If you’re new here, try this 90 second video introduction.

Have you heard the line that “you can have it good, fast, or cheap but not all three?” As a practicing designer, I learned this Venn diagram of impossibility early in my career, at a moment of great stress while my boss was trying to get a client to make more rational decisions by accepting the inevitability of tradeoffs.

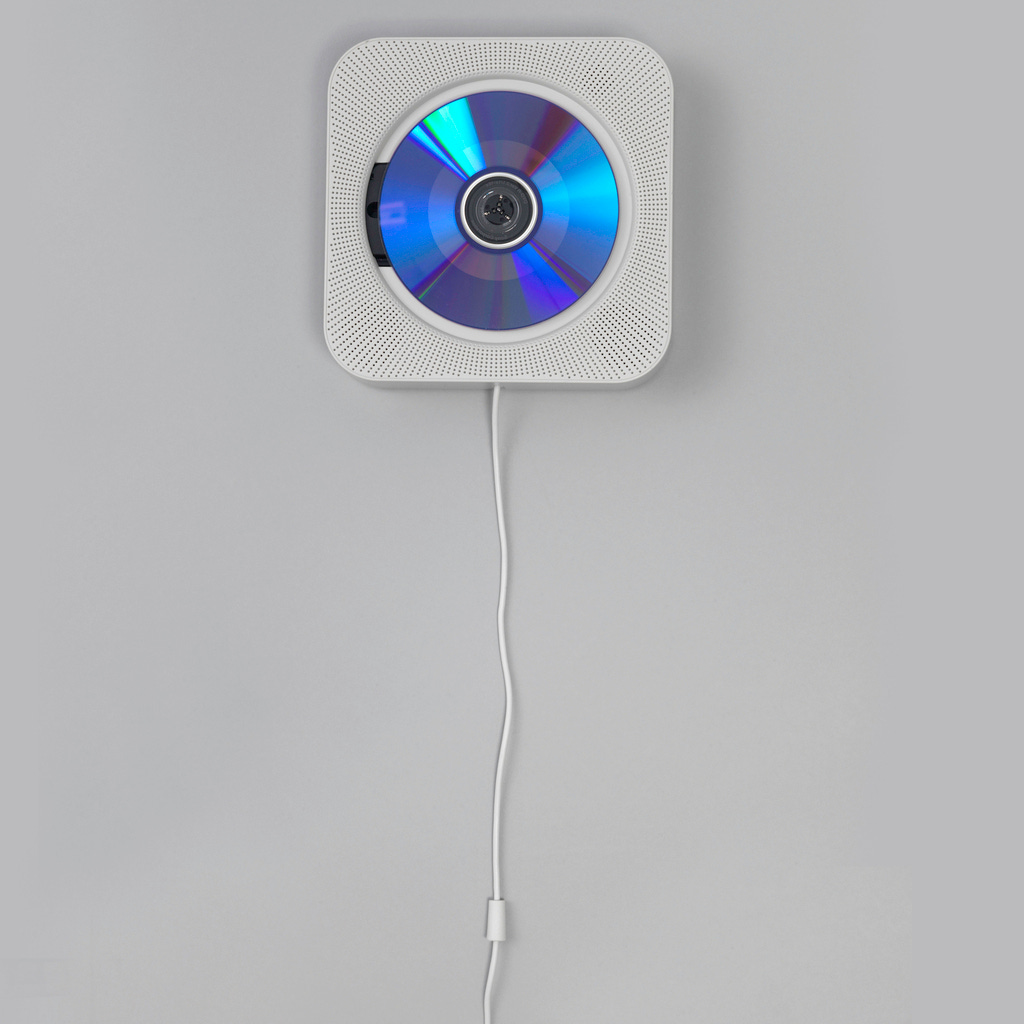

The act of design is usually associated with creativity and aesthetics but, when it’s done well, design is also a unique way of making decisions that evaporates the feeling of loss typically associated with making tradeoffs. Design something well, and tradeoffs don’t feel like a sacrifice. Naoto Fukusawa’s iconic CD player for Muji provides a good example.

Fukusawa’s CD player exposes the CD and replaces the play button with a cable that you pull, like a lamp. The result? The device is playful and memorable, and could be purchased for a reasonable price when it debuted. The clever pull cord design might look like a willful designer trying to create an arbitrarily new way to interact with the media player, but behind this decision was a quest for cost efficiency.

Fewer pieces (no lid, no drawer!) meant fewer materials. Fewer materials = lower cost and/or the ability to spend a little more on the lesser number of elements that remain essential to the device, allowing those pieces to be better and locally made. Fukusawa’s CD player for Muji is affordable, beautiful, and functional and it doesn’t feel like a CD player that is missing something. Rather, it is so carefully designed that it makes all other CD players feel like they have extraneous parts.

In Fukusawa’s design, real tradeoffs were made but they have been transmogrified into upside and no one is hurt in the process. For an urban analog, visit Taipei’s night markets or take a ride down Copenhagen’s bike lanes and then ask yourself why every city doesn’t have the same. Urban tradeoffs are a whole different ball game than well-designed CD players, of course. Getting tradeoffs right in cities is both way harder and far more important.

✅ We Like Urban Technology

By Jonathan Massey

Note: The (lightly edited) essay below is Massey’s contribution to the book Platform Urbanism and its Discontents, part of the Platform Austria exhibition at the Venice Biennale of Architecture (video preview if you’re not into reading). The whole project is worth a look: Peggy Dreamer on the relevance of Elinor Ostrom’s work on commons and governance; Mattia Frapporti contemplating the possibility of political resistance against platforms; the Fairwork Project articulating fairness in pay, contracts, management and more; and AirBnB fever dreams from Bernadette Krejs; just to name a few.

How will we live together? Through the Platform Austria project [at the Venice Biennale of Architecture], the other contributors and I are considering the ways that platform urbanisms answer that question. We are exploring the ways we might occupy, learn from, modify, proliferate, destroy, or replace existing urban platforms to promote our conceptions of the public good.

One path into this topic is through the prompt that Peter Mörtenböck and Helge Mooshammer issued at the start of the project: “We Like.” Drawn from social media practices, this framing invites us to apply the methods of tech platforms recursively to their analysis, as well as to generate insight through appreciation.

Speaking for myself, I like to hail a ride, share a ride, grab an on-demand bike or scooter, understand routing options and times across multiple modalities. I like to rent an apartment or bedroom when I travel so that I can cook, or stay where there aren’t many hotels, or open the window, or share a place with a group of friends. I like to rent out my own place when I’m away. I like being able to instantly identify, evaluate, and select from among nearby restaurants, bars, shops, and businesses. I like connecting with friends and strangers on social media apps. I like being able to consume as much or as little workspace as I like on flexible terms, with a range of amenities and supports at hand, and to make use of a portfolio of spaces ranging from isolated to sociable. I like better building materials and systems, such as mass timber framing, reconfigurable wall panels, digital electricity, and district-scale utility systems. I like municipal services informed by geodata and crowdsourcing. I like learning on my schedule rather than someone else’s. I like the efficiencies and process improvements that big data analytics can generate. I like the potential to automate repetitive tasks and iterative workflows in architectural and urban design. I like outcome-based analytics and decision-making.

What else do I like? Universal healthcare. Workplace safety. Worker protections. Living wages, maybe even guaranteed basic income. Affordable housing. Public transit. Food security. Accessible education. Ethical supply chains. Inclusive forums. Appropriate technology. IRL community. Privacy, especially with respect to state power. Consent. Sharing in the value I create. Equity. Justice.

What else do I like? Universal healthcare. Workplace safety. Worker protections. Living wages, maybe even guaranteed basic income. Affordable housing. Public transit. Food security. Accessible education.

How to reconcile these desires, goals, ethical claims? What about the many others that I have forgotten today but will remember in the morning? What about the needs and priorities of my neighbors, fellow citizens, and fellow non-citizens? Animal species and other nonhuman actors? I don’t always know how to discern, evaluate, and balance competing priorities, or to factor fully the parochialism and privilege that shape my judgment. But I don’t think the status quo is sufficient or sustainable. I’m excited by the prospect of change to our buildings and cities, and to the ways of life that they support. I recognize the uneven benefit and negative impacts of data- and technology-based methods for seeing, shaping, and inhabiting cities. I’m encouraged by the policy responses that are regulating the tech sector, the gig economy, and other data capitalist ventures at multiple scales. I’m inspired by resurgent unions, emergent platform cooperatives, and other forms of worker ownership.

I come to this conversation as a scholar and academic leader trained in architecture and its history. My research has shown how architecture mediates power by shaping civil society, culture, and consumption. During a decade of involvement in the Aggregate Architectural History Collaborative I worked with colleagues to understand how change happens, who authors design, how architecture participates in modernization—how architecture governs. In parallel I took up academic leadership, first at Syracuse University, then at California College of the Arts, and now as dean of the University of Michigan’s Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning. In these roles, I focus on the ways we generate knowledge through research and creative practice and on the methods of teaching and learning that equip students to shape the future.

Many of my former students have entered or engaged the tech sector. They are designing co-working facilities or user interfaces; developing space-as-a-service products, workflow software, computer processing platforms; writing policy and engaging in advocacy to expand access for or limit harm to underserved constituencies. Architectural education gave them powerful abilities such as spatial analysis and imagination, logistical intelligence, humanistic vision, representational virtuosity, and multidisciplinary synthetic capacity. But it didn’t always prepare them to design the lifecycle of a building, product, or service; to use data and algorithms in critical and generative ways; to navigate markets and financial and regulatory processes; or to design services and strategies. Intervening in contemporary urbanization and the platforms shaping our lives requires a set of knowledges, mindsets, and skills that overlap with but also differ from those bundled into an accredited architecture degree.

In order to renew the agency of architecture—the charge issued by chief curator Hashim Sarkis through the Venice Architecture Biennale, and a permanent priority for any forward-looking school—we must remix the discipline’s content, capability, and culture with those of other fields that are increasingly impactful in forming the built environment. This entails engaging proactively with emerging forms of knowledge, tools, technologies, and modes of organization. It requires setting aside some of the topics and skills inherited from prior eras of education and practice. It calls us to carry forward some of our ethical and political commitments while reassessing others in light of new forms of social and economic organization and emergent justice claims.

This is what my colleagues and I are doing at Taubman College. Faculty in architecture, urban planning, and urban design are collaborating with colleagues in other fields and with partners from practice, industry, policy, advocacy, and activism to describe and shape the new field of urban technology. Recognizing that platform urbanism is rapidly reshaping cities and communities, we have developed a new degree aimed at equipping students to accelerate, resist, and modulate data-driven urban transformation. Our Bachelor of Science in Urban Technology will give students the vision, knowledge, and skills to shape urban futures at the intersection of information technology with urbanism and design.

This four-year degree combines thinking and doing, critical reflection and generative praxis. Its courses incorporate a humanist framing of ethics, principles, histories, policies, and urban constituencies; a technical understanding of computation, networks, and data science; and a creative component centering on action through strategy design and service design. By mobilizing data- and technology-based strategies that improve outcomes for city dwellers, graduates will help businesses, governments, activists, and communities address key questions: How does technology help us see and understand cities afresh? How could it help us shape cities through new methods? How might it help us inhabit cities in more fulfilling ways? What policies will promote equitable access and outcomes in cities increasingly transformed by private enterprise?

Our Urban Technology curriculum responds to three patterns in what some term the fourth industrial revolution. First, technology companies are increasingly creating products and services that have spatial, regulatory, and experiential implications in cities. These organizations need a deeper understanding of cities so that they can better address the real needs of urban dwellers in both high- and low-resource contexts. Students who complete our degree will be able to apply their understanding of computation, networks, algorithms, and sensors to promote efficiency and equity, opportunity and inclusion.

Second, urban practices including planning, policymaking, and advocacy increasingly use technological tools such as GIS to understand cities and to regulate technology businesses, products, and services such as autonomous vehicles, delivery drones, face recognition, data privacy, and cybersecurity. These organizations need a deeper understanding of the functions, limits, impacts, and potentials of the technical systems in question.

Third, the disciplines driving platform urbanism, including business, engineering, and information, increasingly employ the collaborative, iterative, and multi-disciplinary methods of discovery and creation at the heart of design education and studio pedagogy. We aim to give the humanist and social scientific approaches of urban studies and planning greater voice in designing urban futures—and also to accelerate the movement beyond the human-centered design methodologies that have powered the rise of design thinking by integrating broader use of quantitative evidence, engaging more directly with technical systems, and centering equitable approaches to co-creation and participation.

Faculty teaching in our existing architecture, planning, and urban design degrees bring much of the expertise behind our curriculum, in many kinds of design as well as urban informatics, collaborative planning, networked urbanism, gaming, crowdsourced urbanism, algorithmic bias, and commoning. We also draw on the knowledge of colleagues from across the University of Michigan in areas such as data science, entrepreneurship, digital studies, and many other humanities fields. We are partnering with companies, policymakers, NGOs, and advocacy groups to connect their knowledge and priorities with our teaching and research.

Many of us are deeply skeptical of platform capitalism and the infrastructures, armatures, and interfaces through which it shapes cities, buildings, and communities. But we see the opportunity and need for research and teaching that center on the intersection of urbanism with technology. We like digging into the contradictions and complexities of the past, present, and future.

So as practitioners and scholars we are analyzing algorithmic bias, helping cities interpret their data, deploying sensors to understand public health, developing space-as-a-service products, making games that teach players commoning. As teachers, we are building our curriculum and preparing to welcome students into the study and practice of urban technology. We orient the many forms of knowledge and skills making up this degree toward enabling students to pursue a mission relating to the urban future. Whether they focus on transportation and mobility, housing, logistics, energy, public health, or another domain, our students will synthesize capacities in urbanism, technology, and design to help the many constituencies with a stake in urban futures live together in a myriad of ways.

Links

🤑 Kevin Roose writes about the upside down economics of many platform companies in the NYT this week, which he calls the “Millennial Lifestyle Subsidy,”

🪵 Katerra again. The Construction Physics newsletter goes deep on the company’s collapse and provides some insight on the internal strengths. Like WeWork, the collapse/stumble of the company is bad for investors and employees but may be very productive for the AEC sector at large as ambition and ideas are freed to find new places to take root.

💌 The Postal Service is one of the most important platforms we have and Brian Justie goes deep on the important role of people as integral to the system in The Nonmachinables.

🕵️ Data can illuminate inequities but leaves out context, writes K.A. Dilday in an opinion piece this week on the limits of data. Pairs nicely with Andrea Cooper’s post on big data and thick data.

⚙️ In “Smart cities, big data and urban policy: Towards urban analytics for the long run,” Kandt and Batty describe the tension between high frequency, realtime big data and the grinding slowness of structural challenges that apprehend urban progress. h/t Rob Goodspeed

This week: Hours spent contemplating the ideal bot to enliven our Discord server for UT students: 0.25; Number of text messages involving discussion of snowballs: 1; Percentage of Friday dedicated to audio simulation of drone-intensive logistics: 33%; Number of faculty who inquired about aspects of the UT program: 4; Seconds elapsed before an experiment with GPT-3 made Bryan cry with laughter (or was it fear?): 30. 🏃